More than thirty years ago, the late artist Wadih El Safi brought tears to the eyes of Fatima, a woman from the southern Lebanese town of Mays al-Jabal. Two years after the war between Israel and Lebanon, she had lost six homes and the memories she had built over three decades.

El Safi sang about the home as a symbol of resilience and connection to the land, stirring feelings of loss and a yearning for belonging in the heart of Fatima Qarout, who was forced to permanently leave her home on October 13, 2023.

“May God be with you, steadfast home in the South” wasn’t just a song Fatima heard; it was a testament to the sacrifices made by the people of the border villages in southern Lebanon during the recent Israeli war.

It painted a picture of a home that, even if its stones were destroyed, would remain alive in memory and fuel a permanent desire to return. Will this desire be fulfilled despite the state’s inability to begin a clear rehabilitation process for reconstruction? Or will Fatima’s destroyed home become a witness to demographic changes that will alter the face of the South and Lebanon over the years?

We lost six homes… and we will return.

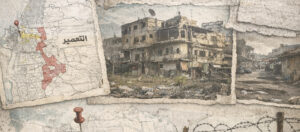

Fatima, who went through two consecutive displacements—the first during the support war on October 8, 2023, and the second during the comprehensive war that ended on November 27, 2024 returned for a quick visit to her village, Mays al-Jabal, seven months after her initial displacement.

During this visit, she said a final farewell to her house, which had been damaged by Israeli strikes, before the enemy booby-trapped her entire neighborhood and leveled her home.

The Israeli war on Lebanon cost Fatima six homes and the memories she had built over three decades.

“We lost six homes that were leveled to the ground. There was one house left standing, but it was burned from the inside with its walls collapsed,” Fatima Qarout told “Sela Wasl,” describing what she and her family felt after seeing the rubble of their homes on maps.

She continued, “It’s hard for a person to see their home destroyed. We were just waiting for the war to end so we could return to our town of Mays al-Jabal. It’s so hard for a person to leave their village, their childhood home, their neighbors. It’s very difficult to adapt to another place that isn’t the village. It’s so hard.”

Fatima consistently refuses to sell her childhood home to build one elsewhere, because of her deep connection to her village.

The enemy has ripped her away from her past and stolen her simplest moments of happiness, like the times she spent sitting outside her home, sipping coffee and waving at passersby with the words, “Welcome, please come in.” Yet, despite everything, she repeats: “Thank God, thank God for everything.

In the face of losing lives, it feels like someone has blocked your emotions. You can no longer think or feel anything.”

When the ceasefire agreement came into effect, Fatima was able to return to Mays al-Jabal, but she couldn’t bring herself to stand for long in front of the wreckage of her home. “I couldn’t stand there for more than two minutes. Everything was destroyed. Entire neighborhoods were ruined,” she said, adding, “But despite all the destruction, I felt safe because I was in my village.”

Despite all the losses, Fatima clings to her right to return to her land, stating, “We are holding onto our lives there. You can’t abandon your land and your homes, even if they’re destroyed.

You have to go up, fix things, and rebuild because you can’t leave it for someone else. The situation forced us to be away, but we will return. We will return to rebuild and reconstruct the South as it was before. These are our homes, and this is our land, and we can’t give them up.”

Reconstruction will not begin before the end of 2025

Fatima’s hopes—and those of others from border villages who have lost their homes—clash with the reality of an unclear reconstruction plan. This is compounded by daily Israeli violations and direct threats to residents, while those abroad are prevented from returning to inspect or settle in their homes.

“The state’s plans will not be implemented before the end of the current year,” said Ibrahim Shahrour, Vice President of the Council for Development and Reconstruction, in an interview with “Selat Wassel.”

He explained, “The council has begun the tendering procedures for consulting offices to prepare the project files, but it will not be able to sign any contracts until the House of Representatives approves the World Bank loan of $250,000, which is part of the required funding for reconstruction.”

The government's goal is to return every citizen to their land, no matter the obstacles.

In this context, according to Shahrour, the government is seeking to secure an additional $750 million out of a total estimated cost of $1 billion for the Lebanon Emergency Assistance Project (LEAP). This project aims to support the rehabilitation of infrastructure and public services in the affected areas.

While Shahrour emphasizes that “the government’s goal is to return every citizen to their land, no matter the obstacles,” the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, through Minister Fayez Rassamni’s office, told “Silat Wassel” that the main obstacle to immediate implementation is “the lack of stability due to the ongoing war, which hinders the actual start of the reconstruction process.”

he Ministry’s office clarified that while it has a plan to gradually restore life to the villages by rehabilitating roads and bridges damaged by the war, it does not include direct intervention in essential infrastructure networks like water and electricity. The Ministry tied the timeline for starting repairs to the current circumstances, meaning that people’s return to their villages depends on the state’s ability to fulfill its promises.

120,000 displaced people in the South and worrying demographic changes.

Today, the southern villages are living a reality not seen in decades. With the ongoing displacement and stalled reconstruction plans, an estimated 120,000 people are unable to return to their homes, according to the International Organization for Migration. This number is significantly higher than what was recorded after the July 2006 war.

The fundamental difference is not limited to the scale of the destruction but extends to its nature and objectives. While the post-2006 period saw a swift launch of reconstruction efforts and a gradual return of displaced people, the destruction in the 2023-2024 war was more widespread and comprehensive.

It even continued after the ceasefire through the booby-trapping and leveling of homes. Dr. Shawqi Attieh, coordinator of the Demography Lab at the Lebanese University, considered this a deliberate attempt to create a buffer zone between us and occupied Palestine, which would be subject to Israeli control.

Following a war that killed between 7,500 to 10,000 people, Atiya notes that Lebanon is approaching the fifth stage of demographic transition. In this stage, birth and death rates become equal. In fact, deaths could even surpass births within the next decade.

He attributes this trend to a series of accumulating crises and emigration, especially since 2019. Births have already dropped from about 110,000 annually 15 years ago to just 66,000. At the same time, deaths rose to 32,000 in 2022 due to the crises Lebanon and the world have faced, compared to a natural average of 26,000 to 27,000.

Lebanon is approaching the fifth stage of demographic transition, where birth and death rates are equal.

Despite this, Attieh believes a slight rebound in birth rates is possible this year. He attributes this to couples no longer postponing having children due to the recent war, in addition to religious and social factors. This increase is a common phenomenon after crises in Lebanon.

Following the end of the Lebanese Civil War, the country experienced a birth rate boom between 1990 and 1995. Individuals born during this five-year period, now between the ages of 30 and 35, remain the largest demographic group in Lebanon today.

Given this complex situation, the South remains part of a country that has, since its founding, witnessed a series of demographic shifts primarily driven by wars.

Fatima’s unwavering commitment, along with thousands of other southerners, to their right of return to their land underscores that this right is non-negotiable. For as Wadih El Safi sang, the home will remain steadfast, even amidst the rubble.