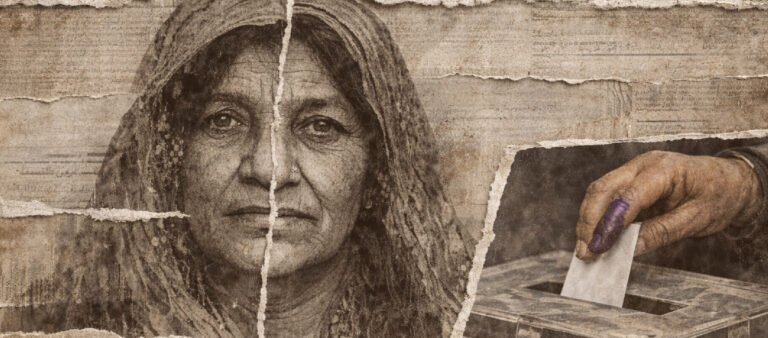

As women grow older, they are treated as though their presence is no longer necessary. This does not happen suddenly, nor through an explicit decision, but through the accumulation of subtle signals: unnamed exclusion, skeptical glances, questions about “capability” and “suitability,” and suddenly imposed limits on what is deemed acceptable or unacceptable. In this way, women are not pushed out of the scene by force, but kept within it-without a clear voice and without genuine recognition.

Within this context, women’s lives are measured by a single standard that nearly reduces their entire existence to youth. As years pass, the body is redefined as less valuable, motherhood is framed as a phase that has “served its purpose,” and an image is constructed that undermines women’s legitimacy for work, independence, and public presence. Meanwhile, men of the same age are granted attributes such as “maturity” and “experience” and are allowed to continue advancing, while women are gradually pushed to the margins-out of the labor market, circles of influence, and the legitimacy of desire and relationships.

Amid this reality, the stories of women advancing in age stand as testimony to a social structure that imposes a single definition of what is “acceptable.” Yet many women have broken these boundaries, continuing their paths in work, education, and public participation, refusing silent withdrawal. In this sense, persistence becomes not merely a personal trajectory, but an act that reveals how what is presented as “natural truth” is in fact an imposed reality that can be questioned and dismantled.

The testimony of Zeinab Fayad emerges as a living example of how aging becomes a tool of compounded exclusion when it intersects with divorce, work, and economic independence.

Age Was Not an Obstacle to Achieving Dreams

Zeinab says: “When I decided to divorce at forty-four, I was not treated as a person who chose to end a relationship, but as a woman who had surpassed the ‘permitted age’ to start over. No one asked why the marriage ended, but why I dared to separate at this stage. The questions were ready-made: Where would I find work? Who would hire a divorced woman over forty? How would I face the economic cost? Divorce was not the problem-my age was. As if personal decisions have an expiration date that must not be exceeded.”

On education, she adds: “At first, I didn’t return to work and study out of conviction, but out of fear-fear of failing in front of my family, fear of the stigma of need, fear of being used as a warning example rather than a role model. Work and returning to university were acts of self-defense against a society that sees women’s patience as a virtue and their choices as a threat. Over time, that defensive motive shifted into a simple conviction: I deserve a better life-academically, professionally, and emotionally.”

“When I decided to return to university, I faced open mockery and unspoken belittlement. There was an expectation that I would quit, as if a woman over forty is not supposed to combine work and education or bear the cost of this path. Failure was anticipated more than success-not because the road was impossible, but because society does not tolerate women who step outside the age sequence it has assigned to them.”

The stories of women who grow older are not individual experiences,

but evidence of a social structure that enforces a single definition of what is “acceptable.”

Zeinab also emphasizes that she was not alone during this phase: “My children, my sister, and my university colleagues formed a real support network that allowed me to continue. I earned my bachelor’s degree and then my master’s in anthropology and launched my writing career. My first novel was published when I was forty-five. Today, after fifty, I have five novels, and the sixth is on the way.”

She concludes: “For me, fifty was not an age of fading, but a stage in which I shed fear and shame and learned to set clear boundaries for my life. The painful losses I experienced during the pandemic reordered my priorities-not toward withdrawal, but toward a life that is less submissive and more honest. In my experience, persistence was not just a personal achievement, but a form of resistance against a system that insists on treating age as a reason for exclusion rather than a source of expertise.”

This structural pattern, hidden behind social norms and dominant discourse, is explained by gender and inclusion specialist Farah Salhab, who argues that women’s aging in our societies is not read as experience or value, but as a social burden.

Ageism Is Not an Opinion: Invisible Gender-Based Violence

Farah explains that “the way women’s aging is perceived remains governed by a patriarchal system that ties women’s value to beauty and reproductive capacity, while men are granted wisdom, authority, and experience as they age. This disparity is not accidental, but the result of an entire social structure that reproduces discrimination and reinforces a wide gap between what is expected of women and what men are allowed to embody.”

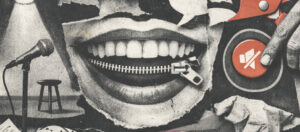

She cites figures revealing the scale of exclusion: “Women represent only a quarter of media figures over fifty, while women over forty-five almost disappear from leading roles, in contrast to the dominant presence of older men portrayed as heroes or central figures. This gap demonstrates how age is seen as added value for men, while it is treated as a burden for women-something to be concealed.”

She also notes that “advertising plays a major role in reproducing these standards: men between fifty and sixty are portrayed as symbols of attractiveness and maturity, while signs of aging in women are framed as problems requiring concealment or correction. This discourse not only creates social pressure, but drives many women into a constant cycle of hiding their age and undergoing cosmetic procedures, out of fear of exclusion and loss of acceptance.”

Men between fifty and sixty are presented as symbols of maturity,

while women’s aging is depicted as a problem requiring correction.

Farah adds that “this discrimination is also reflected in the labor market. Studies show that a large percentage of women over fifty experience marginalization or mistreatment due to age, directly affecting their professional paths. Meanwhile, older men are viewed as ‘veterans’ with valuable expertise. This reality cannot be reduced to social opinion—it constitutes symbolic gender-based violence that excludes women and restricts their public presence.”

Regarding the lack of data on women over fifty and sixty, she stresses that “this absence contributes to rendering such violence invisible, as most research and policies focus on younger age groups, excluding older women from public consideration. This exclusion intensifies when age intersects with other factors such as economic status, education, or displacement-as in the case of older women displaced by recent wars.”

Farah concludes by emphasizing that “future feminist approaches must redefine aging as a stage of experience and value, not expiration-through collecting accurate data, amending laws, and involving older women in decision-making positions.” A living translation of this vision appears in the testimony of Ghada Othman, illustrating how awareness and experience can become tools of resistance and continuity.

Age as a Path of Accumulation and Awareness

Ghada says: “As I grew older, I did not feel my ability to give diminished-on the contrary, my maturity and awareness increased. After forty, my way of thinking changed; I became calmer in my reactions and considered matters from multiple angles before deciding. The difference was not in the number of years, but in the awareness accumulated over time.”

On challenges, she explains: “The biggest obstacle was society’s view of women after a certain age-as if their role ends at the home, as if their capacity to work declines. This perception reflected itself in the labor market, where I faced age-based discrimination, compounded by being a Palestinian refugee woman. Still, I confronted this reality by continuing my work and relying on my experience and performance quality-not on my age or degree alone.”

“Now I am a grandmother. The pressures did not disappear; they changed shape. I faced criticism about my activity, appearance, and choices, but I chose not to let social judgments define my life. For me, age is not a limit to contribution. Persistence itself is an act of resistance and a message that women can redefine their role at every stage of life.”

In this context, clinical psychologist Melissa Abou Zeid sheds light on the deep psychological impact of this system on women over fifty, drawing from real cases that show how ageism and gender discrimination become silent psychological suffering—and how therapeutic intervention can open new spaces for resilience and self-reconstruction.

The Psychological Impact of Ageism on Women

Melissa explains that “the post-fifty stage represents a psychologically and socially sensitive phase for women in Lebanese society, where bodily changes intersect with a cultural system that glorifies youth and ties women’s value to beauty and familial roles. This intersection renders aging a complex experience, oscillating between loss of social recognition and attempts to rediscover the self.”

She notes that “as women age, they carry a cultural legacy linking their value to giving, caregiving, and perpetual beauty. With bodily change and the fading of visible roles, this leads to what can be described as ‘social disappearance’-a feeling that weakens self-worth and reinforces self-denial. Studies show women over fifty are more prone to depression and isolation than men-not due solely to biological aging, but because of compounded gender- and age-based discrimination.”

Media is one of the most prominent spaces where age-based discrimination against women is reproduced.

Psychologically, Melissa adds that “many women experience sadness and loss of value, as if their ‘most useful’ stage has ended, while others succeed in transforming this phase into a space of maturity and freedom by redefining the self beyond youth standards. The crisis is exacerbated by marital expectations and workplace discrimination, resulting in anxiety, depression, and diminished self-confidence.”

She also affirms the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy, narrative therapy, and women’s support groups in restoring a sense of worth and building a more stable identity. She concludes that “positive transformation after fifty requires societal support that recognizes women’s expertise and guarantees their participation-transforming aging from a psychological burden into a stage of balance and meaning.”

Media and Public Life: When Age Becomes a Silent Tool of Exclusion

Gender and sexuality researcher Christine Mehana explains how age turns into an unspoken institutional exclusion mechanism, reproducing stereotypes about who is “allowed” to appear and represent. She argues that media is among the primary arenas where age-based discrimination against women is reinforced-either through direct exclusion or by confining women’s presence to specific age brackets and physical standards.

Mehana notes that “this pattern extends beyond media into workplaces, where many women are sidelined upon reaching a certain age or replaced by younger professionals, as if there exists an unspoken ‘decline age.’ This exclusion not only marginalizes women professionally but undermines their continuity and erases expertise accumulated over decades.”

She continues: “These stereotypes directly affect women’s participation in political and economic life, as many feel that public engagement is ‘supposed’ to begin at a younger age-creating imbalance in decision-making spaces and depriving society of essential female expertise.”

Christine emphasizes that “confronting this reality requires clear institutional policies, the development of labor laws, and an active media role in dismantling discourse that ties women’s value to age or appearance.”

Social Justice Is a Right

The success stories in this report reflect women’s ability to transcend imposed social discrimination, yet their paths remain fraught with challenges that force them into constant proof of their legitimacy to exist and persist within what is assumed to be a “natural” life trajectory. For every achievement, women are re-questioned about their fitness for work, presence, and choice—scrutiny not imposed on men-revealing a structural flaw in the very concept of social justice.

From this perspective, a rights-based approach requires moving beyond describing suffering toward dismantling its structural causes-through explicit policies banning age discrimination, guaranteeing women equal access to social justice, and adopting public policies that account for the intersection of age with gender, class, and economic status, alongside accountability mechanisms to ensure real implementation. Older women are not a marginal group in need of sympathy or exception, but full rights-holders. Delaying recognition of their right to equality and justice is not neutrality-it is a continuing form of violation.