When your homeland turns from a place of safety into a space of fear – from the exile of estrangement to the fire of home: two wars that never end.

From the first moments of the latest war on Lebanon, one question haunted me: How can a person feel safe in a country collapsing around them?

Living between two worlds — in Germany, where I’ve been residing for two years, I watched the news as images of destruction and panic spread across Lebanese towns. I counted the explosions, waiting anxiously for a message to assure me my family was still alive.

For them, war wasn’t just the sound of rockets – it was the daily fear of the unknown.

For me, it was the war of helplessness – the helplessness of an expatriate watching their homeland burn, armed with nothing but silence and prayer.

A Flight into the Unknown

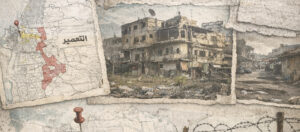

As the shelling intensified, neighbors began fleeing to what they hoped were safer places. Some rented homes in the mountains of Mount Lebanon, others went to stay with relatives in different towns.

My family, however, had nowhere to go. Our home in Kfarkela — a border village in southern Lebanon – the place that had always been our refuge, was destroyed in the first days of the war.

For them, war wasn’t just the sound of rockets,

it was the daily fear of the unknown.

No home, no car, no plan – only survival.

They took a taxi to nowhere, carrying a small bag and hastily packed clothes, hoping to return in a day or two. Their first stop was a town in Iqlim al-Kharroub, one of the areas considered “relatively safe” during the war.

They reached a house belonging to a friend of the taxi driver – empty, unfurnished, and devoid of comfort. That night marked the beginning of a harsh new reality – not only with war itself, but with the people of their own country.

Conditional Hospitality and Painful Discrimination

When the neighbors learned that the newcomers from the south belonged to a different sect, the whispers began.

My sister heard a woman telling her son through the window: “The Shiites have arrived… now this area will become dangerous because of them.”

In Lebanon, a person’s identity is revealed before they even speak – by a cloak, a headscarf, or the color of a veil.

My mother’s black abaya was enough to trigger suspicion and rejection.

The next day, my brother went out to buy some food and returned with insults and hostile looks instead.

Yet amid that tense atmosphere, there was a fleeting moment of humanity: one of the neighbors knocked on the door, carrying a mattress and a blanket, and said shyly, “It’s not much, but no one should sleep on the floor tonight.”

That sentence was a spark of warmth in a cold and lonely night.

But the tension remained.

Before being asked to leave, I had already started searching for another house for my family – the stay there had never felt comfortable.

My mother sensed unease in the stares and veiled remarks of some neighbors.

Then came the day when the owner of the house showed up with an influential man from the village and ordered them to leave immediately:

“Get out of here. We don’t want you here… we don’t want Shiites.”

It happened to be my mother’s birthday that day. My siblings had bought a simple cake, hoping to bring her a little joy amid the suffocating tension.

But the mother who had endured the sound of shelling broke down in tears at the cruelty of words. Her wound remains open to this day.

Exploitation Instead of Solidarity

After days of searching, I came across an ad from a family in the Chouf District offering a room in their house for displaced people – for a fee. At first, the family seemed kind and cooperative, but that didn’t last long.

They charged my parents $700 per month, even though, according to neighbors and residents, rent in that area didn’t exceed $200 before the war.

This sharp increase aligns with a report by ESCWA (August 2024), which noted “a steep rise in housing prices in safer areas due to sudden internal displacement.”

But the exploitation didn’t stop there – some even invented excuses to extort more money: one time claiming the water supply was cut, another citing electricity or maintenance costs.

And so, the humanitarian crisis turned into a silent business – one paid for by the most vulnerable, in a homeland stripped of oversight and accountability.

What my family experienced is not an isolated case – it is a national tragedy.

My family’s story is not unique. The ESCWA report (August 2024) confirmed that internal displacement waves during the latest war were among the largest since 2006, and that the economic and social impacts were felt across the South and the Beqaa.

According to Flash Updates by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), around 578,641 internally displaced persons moved toward their areas of return between November 26 and 28, 2024.

The humanitarian crisis turned into a silent business,

one paid for by the weak in a homeland that has lost its sense of responsibility.

The UNRWA also reported that returns began after the escalation subsided, but they were far from complete due to the lack of infrastructure and essential services.

Meanwhile, local relief organizations such as the Lebanese Red Cross and Oxfam confirmed that many returning families faced significant challenges securing housing and access to services after their return.

These facts confirm that my family’s story is not an exception, but rather a reflection of a deeper crisis within Lebanon’s social fabric – where economic collapse and sectarianism intertwine to form yet another face of war.

Return Without Safety

When my family returned to their home in the southern suburbs on November 28, 2024, they thought it would mark the beginning of peace.

The house was still standing, yes – but the feeling of safety was gone.

The walls were intact, yet fear had settled within them.

Even now, the enemy continues to strike sporadically, and the air still carries the scent of danger.

With every attack, new innocent lives are lost – as if the war refuses to end.

Reports by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) indicate that the calm in the South remains fragile, with serious concerns that fighting could resume if ongoing diplomatic efforts fail.

People in the South live in anxious anticipation; fear of a new escalation dominates daily conversations.

Many whisper that one political or military spark could trigger another wave of displacement – and this time, there might be no safe haven left to run to.

Let Us Restore Humanity Before Rebuilding the Stone

War is not measured only by the number of casualties or the buildings destroyed – but by the despair it plants in people’s hearts.

If international silence continues and security guarantees remain absent, will we face another wave of displacement?

Lebanon does not only need to rebuild the South – it needs to rebuild the trust among its people.

We must remember that survival has no sect, and that sectarianism protects no one.