Lebanon has yet to recover from the shock of the recent Israeli aggression, with its damages and ongoing repercussions, before finding itself facing a new security scene—this time on its eastern flank.

While some southern villages remain at the mercy of the occupation under the pretext of extending the ceasefire, on January 28, 2024, residents of Baalbek–Hermel awoke to Israeli air raids targeting the outskirts of several villages in eastern Baalbek. This coincided with infiltration attempts by armed Syrian groups into border villages in northeastern Lebanon, particularly on the outskirts of the town of Al-Qasr and the Lebanese–Syrian shared areas, where geography and history have been intertwined for decades, but are now being divided and fractured. Prisoner exchanges took place: on one side, Lebanese captives from local clans—specifically from the Jaafar family and one person from the Al-Jamal family; on the other, three fighters affiliated with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham.

In the absence of the state’s security apparatus, the clans of Baalbek–Hermel found themselves in a position of defending their land and lives, facing newly established Syrian armed factions with varying slogans and loyalties, not under a unified command. These factions—described by some media reports as Syrian government forces—seem more akin to militias lacking centralized leadership, bearing the traits of armed groups with diverse affiliations, rather than regular military forces.

The Absent State… and the Clans at the Forefront

As events escalated, there was no official stance from the Lebanese state. The caretaker government, which had negotiated the ceasefire with Israel, did not meet, and the Higher Defense Council did not issue a statement explaining the situation. Only a brief post on the official website of the Presidency of the Republic mentioned a call between the Lebanese president and his Syrian counterpart (during the transitional period), in which they confirmed the need to “avoid targeting civilians”—as if this were merely a family dispute over inheritance, rather than armed clashes on the Lebanese border.

This official vacuum continued until the formation of the new government led by Nawaf Salam, which gave the green light to the Ministry of Defense to assume security responsibility along the Syrian border. By then, the clans had become convinced that “weapons are the only guarantee,” reinforcing a culture of holding onto arms.

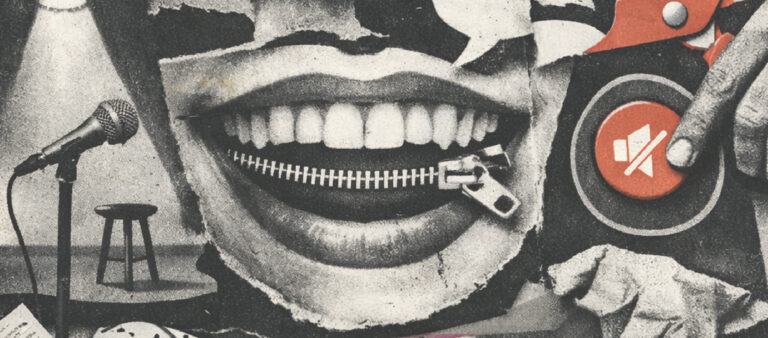

In the “resistance” environment, social media platforms were ablaze with posts glorifying weapons as a solid shield, in what appeared to be an indirect revival of a narrative that has long stirred controversy in Lebanon—affirming the idea that “arms outside the state are the solution when the state abandons its responsibilities.”

This culture has long sparked wide debate and numerous disputes among the Lebanese over the years. President Joseph Aoun addressed it in his inaugural speech, affirming that weapons must be limited to the state and its armed forces. This stance clashes with the recent image of Baalbek–Hermel clans wielding heavy weapons to defend what they consider “purely legitimate” Lebanese villages—raising questions about the extent to which the president’s commitment to monopolizing arms will actually be enforced.

The Army Between Neutrality and Border Control… and Society Facing New Realities

Despite the renewed Lebanese–Syrian border clashes in recent days reaching unprecedented levels—and the fall of several Lebanese martyrs during battles where Syrian groups used drones, rockets, and even tanks, with one shell landing inside the Lebanese Army’s Qaisan barracks near the town of Al-Qasr in border-area Jarmash—the Lebanese Army’s leadership initially chose to remain neutral. More than two weeks after the clashes began, the army command issued strict orders to military units to respond to the sources of fire and restore calm as before.

The importance of these orders, even if delayed, lies in the fact that they came amid a reality in which the Lebanese state faces major challenges in asserting its sovereignty, within a tangled security landscape that requires integrated political and security solutions—especially after Syrian “Shaheen” drones fell on civilian homes in the Lebanese town of Al-Qasr. This incident reopened accusations against Hezbollah and reignited the familiar debate: Was Hezbollah’s intervention in the Syrian crisis justified? And was the Qalamoun battle truly a preemptive move to protect Lebanon’s interior?

Today, supporters of the “Resistance” view these developments as a justification for the soundness of their choices, while another segment of Lebanese see them as a natural reaction to the party’s broad military involvement in Syria.

What was once discussed as political hypotheses has now become a reality on the ground, pushing this segment of Lebanese to hold on to their weapons, which they see as the only guarantee for survival both internally and externally—especially given that Lebanon’s official stance throughout the Syrian crisis was one of neutrality, just as it now remains neutral in the ongoing settling of scores between Hezbollah and the Syrian opposition.

With the fall of the Syrian regime and the party’s withdrawal from Syria, Hezbollah’s base clings to the narrative of holding onto illegal arms more than ever before.

Ironically, the military neutrality policy not only justifies the clans’ and the “Resistance” base’s retention of arms, but also validates the party’s rationale for intervening in the Syrian conflict. Back then, Hezbollah’s main argument was the protection of religious shrines by Shiite armed groups (such as the Fatemiyoun Brigade and Zainabiyoun Brigade), in addition to entering the conflict under two main banners: first, defending Lebanon’s eastern mountain range from the spread of armed factions; and second, defending the regime of Bashar al-Assad. With the fall of the Syrian regime and Hezbollah’s exit from Syria, its base clings to illegal arms more than ever, deepening divisions and fueling a sense of federalized Lebanese nationalism—putting the constitution, Lebanon’s unity, and civil peace at serious risk.

Tensions Crossing the Border… Into the Lebanese Interior

The issue is not limited to security; it extends deep into the social fabric. As clashes along the border intensify, the rift between two communities that had been intertwined for decades grows wider—between the clans of Baalbek–Hermel and the Syrian armed factions, along with the thousands of Syrian refugees living among Lebanese in those areas.

The issue is not limited to security; it extends deep into the social fabric. As clashes along the border intensify, the rift between two communities that had been intertwined for decades grows wider

In some neighborhoods of Baalbek, portraits of Syrian political leaders have been raised—similar to what has happened in northern Lebanon and other Bekaa towns—in a sectarian-charged message reflecting the rising level of tension, amid fears that the rift could spread to the Lebanese street as a whole. On one side is the Syria–Lebanon divide, and on the other is the divide between the authorities and the opposition. The one common enemy that unites both is neglect, corruption, and state collapse—from a Syrian regime that stripped its citizens of their rights to a Lebanese authority notorious worldwide for corruption and the looting of depositors’ funds. The question remains: how long will the Lebanese and Syrian peoples continue paying the price in blood?

Today, Baalbek–Hermel is not just a battlefield; it is a mirror reflecting the dilemma of the Lebanese state as a whole. In the context of the new political order, the question of sovereignty becomes a major challenge against the backdrop of fast-paced events in the Middle East.

Securing the border and not leaving it in the hands of the clans is an essential task—especially amid calls for national unity, even as divisions grow ever deeper.

This article does not necessarily reflect the views of the website.