“I’m afraid if one of the kids gets sick, I won’t know what to do,” she says.

The fear of illness is natural, but since this sentence is stripped from its context, let me clarify: the fear is not of the illness itself as much as it is of the cost of treatment.

This is not a quote from Hugo’s Les Misérables, nor from Taha Hussein’s The Tormented on Earth.

It’s an ordinary conversation on public transport on a Tuesday morning, with no remarkable events—except that people can no longer afford to live.

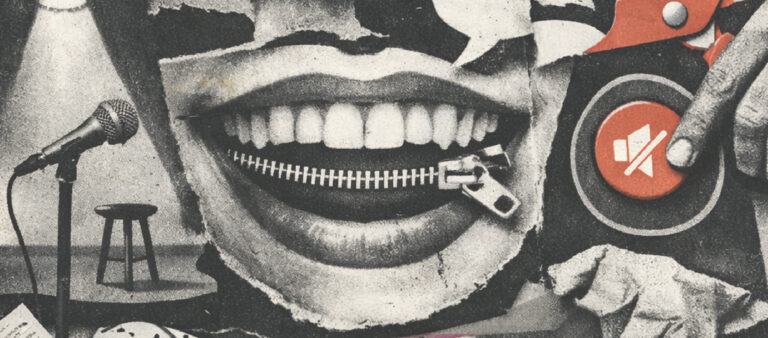

In the absence of genuine national journalism that speaks for the people, there is no other way to hear their voices but through themselves.

And that is exactly what we will do now: we will listen.

And if you don’t believe me, try taking off your headphones and hear what’s going on around you—in the street, at work, at university, even at school.

The sense of distress is widespread, affecting every segment of society.

In the absence of genuine national journalism that speaks for the people, there is no other way to hear their voices but through themselves.

Today, I chose to listen to what’s being said on public transport—specifically the bus.

Its long ride helps break the ice and open conversations.

The only difference now is that the place that once echoed with funny stories, football banter, maybe a few religious debates, and harmless gossip that never crossed the bounds of Egyptian family decency, now is either blanketed in heavy silence or filled with sad conversations.

Curses are now the most common sound on the bus.

Every time a passenger hears the new ticket price—three pounds higher overnight—you can see the frustration hit their face.

A fleeting look of helplessness appears, they glance at their money with regret, knowing they won’t get any change back, and perhaps will have to add to it.

They end up paying the fare and sinking into a sea of calculations: this same increase will hit them again on the way back, every day, for every family member.

It adds up to nearly 700 pounds a month on a fixed salary that hasn’t risen by a single pound.

This inner conversation always ends with another curse.

Then there are other conversations—not internal, but spoken aloud—between two people bold enough to complain in public.

Even complaining has become suspect; your grievance could land you in an opposition prison.

You hear one employee speaking with a tone of fake triumph masking his frustration:

“Every day I walk to the start of the street and the same thing on the way back. Not worth the six pounds I’d spend otherwise. The whole thing just needs me to wake up half an hour earlier. At the end of the day, I’m exhausted, but we spend the ride reciting prayers so it passes quickly. By the end of the month, I’ve saved about 200 pounds—that’s enough for two private lessons, a kilo of chicken breast… little savings like that make a difference.”

Even complaining has become suspect; your grievance could land you in an opposition prison.

The conversation ends with his colleague wishing him patience and endurance, secretly grateful that the bus stops right under his building, sparing him the six pounds and the extra hour.

In another conversation, there’s no fake triumph—only complete defeat.

You hear a man telling his colleague how, with great reluctance, he pushed his son into working because university costs have overwhelmed him.

His voice carries the weight of unshed tears:

“His older brother begged me to let him work with some friends, but I swore he wouldn’t take a job until he finished university—so I’d never have one of my kids come to me one day saying I failed them.”

He pauses, thinking about the 40 years he has lived as a father proud of himself, never imagining that he’d be broken in the final stretch.

What worries him most is that he might one day have to push his daughter into work too.

After this last blow, for the first time in his life, he no longer sees safety in this world—and thanks God that what remains of his life is far less than what has passed.

Sometimes you might stumble upon a lighthearted quarrel over an empty soda can and think the morale hasn’t completely collapsed.

But once you learn the reason, the sadness deepens.

It began when a woman asked her colleague for the empty can she had just finished drinking, explaining that she now collects cans to sell—about 50 pounds per kilo to a scrap dealer—though their real value is nearly double.

Unfortunately, she has no direct access to the big traders, so she has no choice but to work through a middleman.

Her colleague’s eyes first showed admiration for this resourceful woman who knows how to scrape together money.

But moments later, that admiration turned into sorrow, pity, and a touch of compassion as she began to explain how she gathers those cans.

Public transport is no longer just a means of getting from one place to another—it has become a means of release, a form of confession.

It’s the confessional of the poor, who have no one to listen to them but each other.

She might sometimes keep one she has just drunk from, but more often she is forced to collect empties from anywhere she finds them—a can tossed on an office desk, or one lying at her feet on public transport.

Sometimes it takes more effort, and she’ll quickly take an empty from a colleague under the pretense of throwing it away for her.

At times, she’ll even shyly send her son to pick up one lying on the sidewalk because she cannot bend down herself—though inflation has already forced her to bend in other ways.

That quarrel we glimpsed at first was, in truth, a struggle for dignity, not for metal.

These conversations are spoken with a tone of acceptance and resignation, for everyone knows the situation is a fate from which there is no escape.

The common thread in all these exchanges is that no one is asking for much anymore—only that life not grow harsher still.

On every trip, the bus moves on, conversations flow, and with each stop, hearts grow heavier.

Public transport is no longer just a way to get from one place to another—it has become a way to let off steam.

It is a kind of confession, the confession of the poor who have no one to listen to them but each other.

And that alone is reason enough for us to listen.