A Joint Report by Tamara Emad and Manar Al-Zubaidi

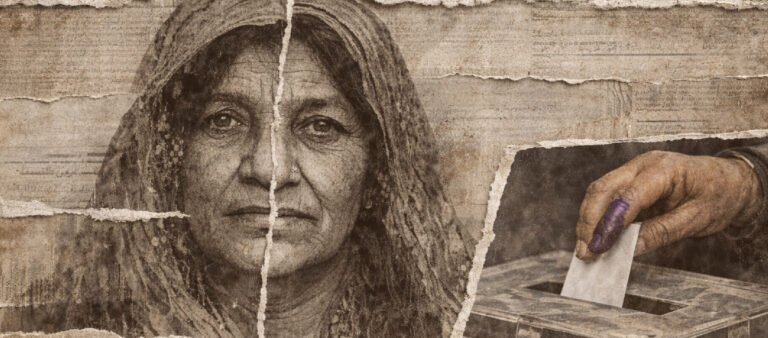

In the village of Al-Zuhoor in Al-Diwaniyah province-about 180 km south of Baghdad-all colorful political promises collapse with the first rainfall. The true test of democracy here is whether the “promise of gravel” can withstand the mud. Here, forty-year-old Um Karim traces her daily route between her home and the school where she works as a cleaner, her steps heavy. She chases not only a livelihood she recently earned after years of unpaid labor, but also a homeland that has given her nothing more than dried purple ink on her finger every election cycle-never once paving her promised road or rescuing her voice from being bartered for a loaf of bread.

Between the school’s narrow corridors, Um Karim grips her broom and her national ID card at the same time. The card grants her the right to vote as a passing electoral number, yet it can also strip her of the label that determines either her integration or her permanent exclusion-under a merciless social and legal stigma.

This is the story of citizenship mortgaged to a field in an electronic form. Roma women in Iraq face compounded marginalization that turns their voices into ink on paper and their fingerprints into mere deeds for bargaining survival at its bare minimum.

Roma women in Iraq are pursued by a social stigma tied to their community’s history in art and dance. This stigma renders their bodies violated in the public imagination, exposing them to harassment and various forms of exploitation.

Researcher Ferial Al-Kaabi argues that “Roma women are subjected to social discrimination due to their ethnic belonging, making them easy targets for all forms of violence. This inferior perception prevents political parties—even those claiming to be civil—from nominating a Roma woman on their lists; her roots alone are enough to exclude her due to societal attitudes.”

Legal researcher Abbas Al-Rubaie says: “Because of systematic stereotyping, any party or political entity fears for its electoral reputation if a Roma woman is nominated, sacrificing her right to political participation on the altar of prevailing social norms.” This fear, however, quickly disappears when Roma women’s votes are exploited to support those same party lists.

From the Iraqi government’s perspective, Roma people are not recognized as an official minority under the constitutional framework;

they are treated as a “marginalized social group.”

Legally, and from the Iraqi government’s standpoint, Roma are not considered an official minority and are treated as a “marginalized social group.” This designation is not merely linguistic-it is a legal denial of cultural specificity, depriving them of minority protection mechanisms and political quotas granted to other groups such as Christians and Yazidis, according to experts. On minority affairs, explains Saad Salloum.

Article 125 of the Iraqi Constitution states: “This Constitution guarantees the administrative, political, cultural, and educational rights of various nationalities such as Turkmen, Chaldeans, Assyrians, and other components, and this shall be regulated by law.” The constitutional legislator listed specific groups as examples and used the phrase “other components” to cover the rest.

In legislative and practical applications following the Constitution’s adoption, “other components” came to include Yazidis, Shabak, Sabean-Mandaeans, and Faili Kurds-explicitly recognized in later laws. In contrast, no judicial interpretation by the Federal Supreme Court nor parliamentary legislation has included Roma under this umbrella.

Salloum notes that the absence of legal recognition of Roma as a “component” with collective cultural rights entrenches exclusion rather than addressing it. The state treats them as a “social problem” to be contained, not as citizens to be integrated.

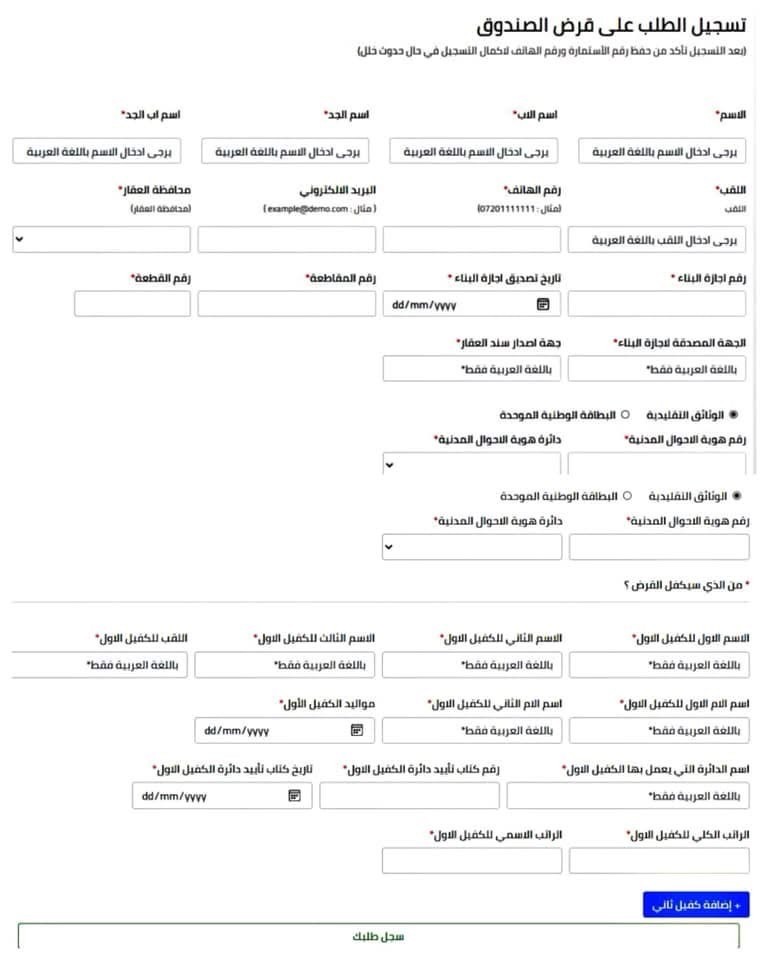

Digital Citizenship: The Minefield of a Missing “Surname”

Exclusion begins with official paperwork. Abbas Al-Rubaie explains that while the Iraqi Constitution-particularly Article 14-establishes equality and considers nationality the basis of citizenship, and while the Ministry of Interior in 2019 removed the phrase “exempt from the Personal Status Law” from nationality certificates, the stigma did not disappear from civil digital records. In many cases, the label “Roma” remains embedded in electronic fields.

Al-Rubaie says: “In the era of digital transformation, the surname field has become a major problem. Many Roma have ‘Roma’ written in that field; the lucky ones find it left blank.”

When a Roma woman applies for employment or a loan through electronic portals, the system rejects her because the surname field is mandatory. She faces two choices: enter false information and risk legal accountability, or be denied the service. This gap is not merely technical—it embodies incomplete citizenship. The state issued national IDs but failed to protect them from social norms that turn origin into a stigma blocking employment or candidacy.

“Good Conduct” as a Tool of Political Exclusion

The “good conduct and reputation” requirement in election and party laws is among the most dangerous legal obstacles facing Roma women’s political participation. Party affairs expert Ahmed Al-Khudairi explains that ethnic belonging is innate and should not affect “good conduct.” Yet in practice, authorities may interpret a Roma woman’s background-linked historically to dance and music, deemed immoral by tribal and religious norms-as a “deficiency in good conduct.”

Al-Khudairi argues that this vague condition grants discretionary power to decision-makers, turning Roma identity itself into an unwritten moral charge that women must prove themselves innocent of-a burden no other candidate faces.

Votes for Barter and Wills Mortgaged by Proxy

In Al-Zuhoor village, Mukhtar Fares Al-Moussawi reveals a reality where democracy becomes a hollow ritual. Women are mobilized as tools to improve men’s and families’ conditions. This manifests as forced political proxy voting, where a guardian-father, husband, or brother-dictates the candidate, openly confiscating women’s independent will.

This dependency is not merely social custom but part of patriarchal deals between families and certain candidates. Men claim to boycott elections as protest, while sending women to polling stations to execute bargains for small sums or hollow promises-like repairing a school or covering roads with “gravel.”

According to Al-Moussawi, educational gaps enable this exploitation. Illiteracy among female voters in the village reaches roughly 75%, turning them into a compliant electoral reservoir detached from political programs or candidate engagement.

Illiteracy among female voters reaches approximately 75%,

turning them into an easily manipulated electoral reservoir.

Noor Samir (pseudonym) embodies this tragedy. A woman in her forties without even a documented birthdate, she summarizes her relationship with the ballot box: “We vote for the cash promise because we have lost hope in all others.” Elections, for Noor, are not citizenship but a forced response to those who purchase her misery for a few days with a ballot.

The promise of “gravel” was the price Um Karim and her friends received for their votes—before discovering its emptiness. She recounts simply: “They promised paved streets. We voted. In the end, the roads remained mud, and the school stayed isolated.”

Here, ballot boxes become not instruments of change but a political slave market, auctioning the poorest women’s voices for meager prices—promises that are, in essence, rights never fulfilled. Citizenship begins and ends at the threshold of material need.

Roma Women and International Commitments: The CEDAW Gap

Iraq has ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and adopted UN Resolution 1325 on Women, peace, and security. But how does this apply to Roma women?

Article 7 of CEDAW obliges states to eliminate discrimination against women in political and public life.

From a feminist legal perspective, Ferial Al-Kaabi argues that what exists is symbolic rather than substantive participation. Iraq, as a signatory to CEDAW and Resolution 1325, is obligated to include all women. Excluding Roma women reveals a gap between international texts and practice: Roma women suffer compounded discrimination-as women and as Roma-where their rights end at casting a ballot and never begin at decision-making tables.

Academic and women’s rights specialist Bushra Al-Ubaidi agrees, describing the situation as a blatant constitutional violation. She calls for a legislative revolution to reform laws using inclusive language, stressing that improving Roma women’s legal status must start from Article 14 of the Constitution, ensuring full equality for Roma women as Iraqi citizens.

Article 14 of the Iraqi Constitution: Iraqis are equal before the law without discrimination based on sex, race, nationality, origin, color, religion, sect, belief, opinion, or economic or social status.

Al-Ubaidi emphasizes the need for legislative and educational revolutions to address Roma women’s conditions and secure equal treatment without discrimination, ensuring their rights under international and constitutional frameworks.

Our investigation found that published data reveal weak solidarity from the Iraqi feminist movement toward Roma women-particularly in shadow reports submitted to CEDAW. Roma women are rarely included in civil society programs or national plans implementing Resolution 1325. There is “no dedicated space for Roma women’s suffering,” leaving them isolated even within feminist and civil activism due to taboos and stigma.

Will a Roma Woman Ever Run for Office?

Iraqi election law requires educational qualifications for candidates. Given state and societal marginalization of Roma communities, school destruction in Roma areas after 2003, and exclusion of Roma children from nearby schools due to parental objections and lack of state intervention, educational access remains severely limited.

Children of Al-Zuhoor returned to school only in 2017 after an advocacy campaign titled “Roma Are Human,” which succeeded in opening a primary school and securing national IDs. Despite limited psychosocial support, most Roma women remain illiterate or barely literate.

Um Karim says: “If I finished my education, I would run.” Her job as a cleaner and her education level-sixth grade-render her political ambition legally impossible.

Running for office in Iraq requires vast financial resources for campaigns-resources Roma women lack due to extreme poverty and discrimination in employment.

Funding shortages are decisive, notes Abbas Al-Rubaie. Even if education and will exist, political money seals the door. While the law allows choosing a non-stigmatizing surname, collective social scrutiny still searches roots to exclude the other.

The issue of Roma women in Iraq is the true test of the state’s seriousness in applying “equal citizenship.”

It goes beyond quotas or representation; it begins with cultural recognition and criminalizing discrimination based on surname, origin, or ethnicity.

Roma women in Iraq face compounded discrimination: oppressed as women in a patriarchal society, as Roma in a racist society, and as poor under a rentier capitalist system.

Between Um Karim’s broom and the ballot boxes, the rights of women holding Iraqi nationality yet lacking existence are lost. Empowering Roma women begins by removing the stigma of “conduct” from their origins and enabling digital systems to recognize them as citizens without imposed labels—or with surnames they choose themselves, beyond tribal customs and the shadows of enduring injustice.