With a mindset far removed from any notion of enlightenment-echoing Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi’s The Nature of Despotism and the mentality of the strict “patriarch” who fears losing control-the Lebanese government received comedian Mario Mubarak at Rafic Hariri International Airport. It was not a reception, but a “disciplinary slap on the wrist”: his phone and passport were confiscated, and he was sent to the so-called “rat room,” from where he entered a spiral of interrogations on charges of “disobedience.”

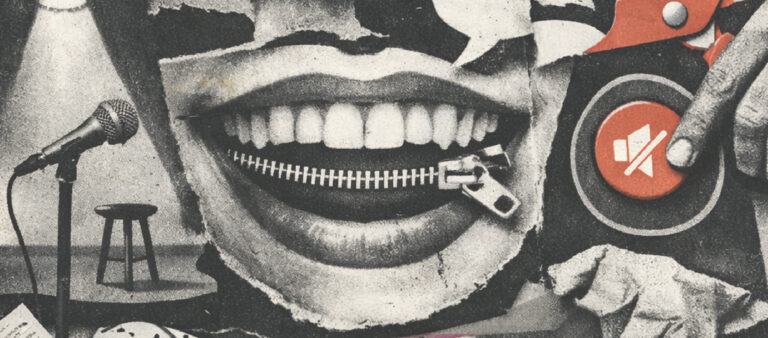

Mario’s ordeal began with the circulation of a short, edited clip taken from a stand-up performance that had been published in full months earlier on Awkward, a Lebanese stand-up comedy platform. The excerpted video contained a joke that some interpreted as mocking the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. Its resurfacing coincided with the approach of Pope Leo XIV’s visit to Lebanon. As the clip spread, Father Abdo Abu Kasm, head of the Catholic Media Center, appeared on television calling for Mario and others like him to be held accountable, claiming the timing of the joke was deliberate. This fueled social media agitation, with incitement posts, death threats against the young comedian, and the leaking of his phone number. Yet since the original video had been published more than six months earlier, the question remains: who benefited from recirculating the clipped video at this particular moment?

The timing seems to have been ideal to turn Mario into a scapegoat-not because of what he did per se, but because of what he represents in gendered terms. He was cast as a “folk devil” to manufacture a directed moral panic-a concept coined by American sociologist Stanley Cohen-used to discipline bodies that deviate from prescribed gender roles and to punish any departure from the obedience and conformity demanded by the patriarchal order.

Moral panic is not merely a social reaction,

but a gendered tool of power that activates fear to regulate behavior.

In this context, moral panic is not simply a social response, but a gendered mechanism of authority that mobilizes fear to control behavior and draw boundaries between what is permitted and what is criminalized-especially when it comes to bodies perceived as rebellious, undisciplined, or symbolically “contagious.”

Moral panic occurs when an individual or group is presented as a threat to dominant values-not necessarily because of the act itself, but because it violates accepted norms. Here, moral panic intersects with the concept of hegemonic masculinity, as theorized by sociologist Raewyn Connell, through which behavior and bodies are re-disciplined according to a normative masculine model presented as natural and legitimate. Even after the panic subsides, stigma and stereotyping persist, particularly against those who do not conform, and mechanisms of symbolic subjugation continue long after the campaign ends.

Ammar Ahmad, a lawyer and human rights activist, argues that what happened to Mario and Shaden cannot be separated from a broader structure of repression disguised as law. He explains: “In Lebanon, authorities do not punish the act as much as they punish disturbance. A joke becomes a crime only when it disrupts power balances or embarrasses religious or political authority at a sensitive moment.” He adds that the vagueness of “blasphemy” and “incitement” provisions allows them to be used selectively-invoked when needed to discipline voices that stray from obedience, rather than to protect civil peace as claimed.

The cases of Mario and Shaden do not appear to be isolated incidents,

but recurring chapters in an ambiguous relationship between power and humor.

During moments of political or economic tension, multiple experiences show how cultural or artistic issues are transformed into focal points of public controversy-often at the expense of more urgent debates about economic policy or social rights. In Lebanon, this pattern was clearly visible in 2019, when the campaign targeting the band Mashrou’ Leila coincided with the peak of the economic crisis and ended with the band being banned from performing in the country.

This is how some fathers in our societies behave: they sense the smoke as their children pass by, see them with friends they disapprove of, yet remain silent. But when they feel cornered or accused of something, they unleash their rage over what they had previously ignored. The ledger comes out, the archive is reviewed, and the children are told they are the source of all misfortune. Punishment, however, differs from one child to another-depending on their position within the patriarchal hierarchy.

Maya Awada, a researcher in gender and cultural studies, links the suppression of humor to patriarchal hierarchies. She argues that “satire—especially when it comes from women or queer individuals—threatens the symbolic order more than any direct political speech, because it strips power of its sanctity and exposes its fragility.” She notes that violent reactions stem not from “offending the sacred” per se, but from breaking hierarchy: who is allowed to speak, who is expected to remain silent, and who is permitted to “laugh outside the house.”

In this sense, the cases of Mario and Shaden are not individual anomalies, but recurring episodes in a troubled relationship between authority and humor. The father, like the system, may tolerate mistakes or overlook slips-but he does not forgive being laughed at. As Mikhail Bakhtin writes, laughter does not confront power directly; it drains it of its aura and turns it into an object of ridicule. When the “son” or “daughter” laughs out of script, punishment becomes not an option, but a necessity to reassert order.

A father’s treatment of a child he deems disobedient varies. What may be dismissed with a “twisted ear” for a young man who slipped once can escalate into total estrangement and expulsion for a daughter who defied patriarchy and attacked it openly. Before Mario, queer Lebanese stand-up comedian Shaden Fakih had already been subjected to similar demonization. A clip of her joke commenting on Friday prayer circulated online, triggering incitement campaigns and death threats. The government imposed a travel ban on her while she was on a comedy tour in Canada, leaving her with no choice but voluntary exile in France amid escalating attacks-facilitated by government negligence and complicity.

When the “son” or “daughter” laughs out of script,

punishment ceases to be a choice and becomes a necessity to restore the system.

Thus, while Mario’s case ended with the release of a police officer after a public apology, Shaden’s case did not follow the same path. Despite similarities, the charges differed. Mario was accused of insult, blasphemy in the name of Christ, and offending religious sanctities, while Shaden faced additional charges, including inciting sectarian and religious strife and undermining national unity. This invites scrutiny of the deliberately vague legal definitions of blasphemy and incitement in a country where extremist groups are not held accountable for overtly racist and hateful speech-yet legal ambiguity remains a tool of repressive systems, enabling accountability whenever authorities see fit.

Shaden’s accusations did not stop at alleged blasphemy. Patriarchy, as always when a woman is criticized, retaliated through her “honor.” Social media “strongmen,” echoing their patriarchs, launched smear campaigns. Sheikh Hassan Meraab from Dar al-Fatwa labeled her vulgar and disobedient, and followers amplified his words. Shaden represents a “double deviance,” according to sociologist Frances Heidensohn’s theory: women receive harsher punishment because they deviate both from socially acceptable behavior and from gender norms. Thus, as one moves further from the apex of the power hierarchy, the number and weight of accusations increase.

The patriarch may overlook his children’s slips as long as they display obedience-but pure mockery of him and the power system he enforces is a red line that demands punishment to prevent escalation.

In Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin argues that carnivalesque laughter temporarily frees us from the established order. Its power lies not only in defying death, but in defeating power, kings, social hierarchies, and all forms of oppression. This is precisely why satire unsettles patriarchal systems: it strips them—even momentarily—of the power they constantly reinforce. What, then, if the one who mocks is a woman—exposing the patriarch’s imaginary authority and shaking the throne of his masculinity?

The strength of the repressive patriarch lies in his belief that he controls his children. He is thus shocked when one breaks ranks, a wound that tightens his grip on the rest. But where does this power go when all the children refuse to play along? Perhaps no promise is fulfilled—but the limits of power itself are revealed. Power rooted in hegemonic masculinity depends on obedience as a given. When recognition is withdrawn, power loses its core condition. The joke then shifts from a tool of sarcastic discipline to an act of exposure—disrupting domination’s logic and redistributing meaning beyond its terms. Laughter becomes a space of resistance, not a reinforcement of authority, but its undoing.