“We plant because the land is our life.” This sentence captures Umm Ali’s relationship with her land and reflects the bond between the people of the South and their soil. When Umm Ali returned to her fields, she insisted on restoring life to land devastated by Israeli shelling. She had lost her husband to that bombardment, yet she chose to confront war with life despite every loss.

Like Umm Ali, women and men farmers returned to their land because agriculture is a right to life and livelihood, and a way to hold onto identity. Yet farming in the South now carries environmental and food related risks as a result of what the war left behind. Farmers find themselves facing a new battle: protecting the land and sustaining life in a war whose consequences did not end with the ceasefire declared on November 27, 2024.

Fatima Shehab, known as Umm Ali, a seventy year old farmer from Bazouriyeh, recounts her story. “My role in agriculture changed after the war. I carried new responsibilities within the family after my husband was killed. My home was destroyed, and we lost our lemon and citrus crops, which were our source of income. When we returned, I discovered that the water pump and the artesian well used for irrigation were damaged. I had to start everything from scratch.”

The agricultural sector in Lebanon was among the most severely affected sectors, despite being a pillar of food security and livelihoods.

She continues, “My sons have no farming experience, so I had to take over the land. I used to help my husband with my own hands. After we returned, I assumed full responsibility. We cleared the land, removed the rubble, and I started planting again. I cultivated about half of the land, including vegetables.”

Fatima says that the absence of protection and support is the main problem. “Planting one plot of land cost me more than four to five thousand dollars between seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, labor, and plowing. Meanwhile, crops like cabbage generate only a few hundred thousand Lebanese pounds per crate. I have not received any real assistance, even though more than a year and three months have passed since we returned. Official registration procedures prevent me from benefiting from support programs because after my husband’s death, the land was transferred to the heirs.”

She continues plowing, planting, and irrigating despite her age. She describes women’s agricultural work as labor without rights. “We receive no health coverage, no social security, no pension. Supplies are priced in dollars while production is sold in Lebanese pounds. I could not even afford soil testing, so I limited myself to plowing and clearing. What we need now is real support for agriculture. If things continue this way, no one will plant. I plant because the land is our life and to keep my husband’s memory alive within it.”

Umm Ali’s story reflects the reality of many villages affected by Israeli attacks on Lebanon that have not ceased to leave their mark. From her story, we move to others and shift the environmental and food lens toward what the war left in the soil and what farmers face as they attempt to continue farming and living.

What Will We Plant and What Will People Eat

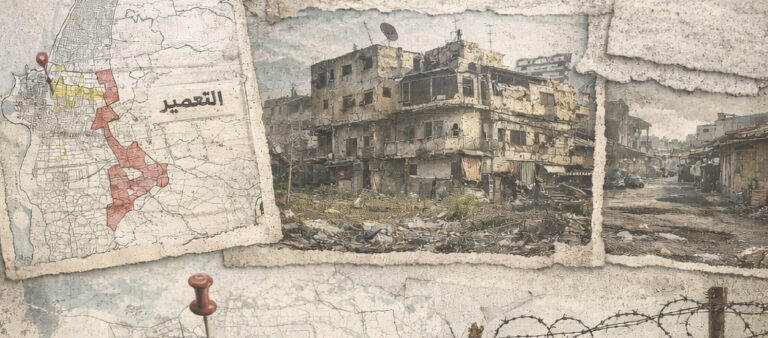

A United Nations Development Programme study published in December 2024 on the social and economic impact of the recent war on Lebanon found that agriculture was among the most affected sectors, despite being essential to food security and livelihoods, particularly in South Lebanon, Nabatieh, the Bekaa, and Baalbek Hermel.

The study indicates that agriculture, which contributed around 8 percent of GDP after the 2019 economic collapse, suffered widespread disruption due to shelling, fires, and the loss of planting and harvest seasons.

A total of 2,193 hectares of agricultural land and pastures were damaged, including 1,917 hectares of forests and 275 hectares of farmland, with the complete loss of 134 hectares of olive groves. More than 12,000 hectares of farmland were abandoned in South Lebanon and Nabatieh. Missing two olive harvest seasons in 2023 and 2024 resulted in an estimated production loss of 26,000 tons, leading to a local olive oil price increase of approximately 60 percent compared to 2022.

Women at the Center of Loss: Essential Labor Without Protection

According to the report, these losses do not fall equally. Their impact weighs more heavily on rural women who form the backbone of agricultural labor, particularly in harvesting, seasonal work, and non timber forest products such as bay oil, carob molasses, thyme, and sage.

Displacement, fires, and restricted access to land and forests disrupted this source of income. Many women lost their ability to secure independent earnings. Those who returned to the land did so as a sole means of survival, deepening economic vulnerability in the absence of protection or support.

Local soil health practitioner and educator Hadi Awada explains that shelling across agricultural areas raises concerns about chemical residues and trace metals left by munitions, such as phosphorus, and their potential impact on soil, water, and crop quality. He notes that assessment depends directly on the types of weapons used. Available information indicates the use of white phosphorus in several locations, as well as artillery shells that typically contain explosive materials such as TNT and trace metals that, upon detonation, may settle in soil or enter the ecosystem.

Awada highlights concerns regarding bunker buster munitions and the possibility of their use. These weapons may contain depleted uranium to enhance penetration capacity. Detecting such contamination is extremely difficult due to the intensity of explosions that mix soil at various depths, making it scientifically complex to identify residue locations or confirm their presence. He also notes the presence of other heavy metals such as aluminum.

Tobacco as an Example: A Crop That Absorbs Heavy Metals

Awada emphasizes that the central risk lies in the fate of these materials: whether they remain in soil, seep into groundwater, or are absorbed by crops and enter the food chain. Tobacco is cited as a clear example, as it naturally absorbs heavy metals such as lead and cadmium. Tobacco continues to be cultivated and sold without laboratory tests confirming whether dangerous residues exist. The goal, he stresses, is not to alarm people or question farmers, but to urge the state to assume responsibility through systematic testing and monitoring mechanisms.

What is required is not informing farmers that their land is contaminated and rejecting their production, but implementing mechanisms such as purchasing crops within a system of tracking and testing. A scientific approach to lands showing elevated heavy metal levels can support farmers while protecting consumers.

Awada notes that the scale of testing required is vast due to the extensive affected areas from the border strip to the Bekaa, Baalbek, Tyre, Nabatieh, the southern suburbs, and Beirut. A scientific methodology to identify hot spots is essential, especially with winter approaching, as rainfall and soil movement may redistribute contaminants.

Attempts at Remediation Without Institutional Framework

Awada states that direct remediation efforts are currently underway, particularly in border areas, without effective cooperation from the state. Meetings and appeals since the start of the war have not translated into public policy or structured institutional action.

“We are working on olive lands in areas such as Kfar Kila, Khiam, Marjayoun, and Deir Mimas as pilot models. We produce compost, prepare microorganisms, and monitor soil periodically to gather scientific data on potential improvement. Olive cultivation is essential in the South, and if we develop a suitable biological formula, it can later be expanded.”

All of this occurs under extremely difficult security conditions, especially in border regions where danger persists, preventing many farmers from returning. “Our family had olive land with about 120 trees, eighty years old. It was completely bulldozed, as was the entire hill. No compensation, no follow up.”

Our family had olive land with about 120 trees, eighty years old.

It was completely bulldozed, as was the entire hill.

Here lies the core of the issue. The loss is not merely material. Eighty year old trees cannot be compensated with money. A village’s history, heritage, and memory cannot be replaced. Reconstruction must include restoring what is old to preserve identity.

Awada explains that he returned to his village about a year before the war after years of agricultural work elsewhere. He began planting mulberries using biological agriculture methods aimed at reviving soil through microorganisms that support plant growth, enhance water absorption, and reduce irrigation needs. This approach preceded the war and emerged from structural issues in the prevailing system based on intensive plowing and chemical spraying.

Returning Without Protection: Fear of Repeating 2006

With the war and use of phosphorus, Awada says the question resurfaced strongly: what will return look like after war. He warns against negligence, as people return without protection, inhale contaminants, and drink polluted water, potentially leading to increased disease rates similar to what followed 2006. Soil treatment approaches rely on biological methods involving bacteria, fungi, and nematodes, along with thermal composting and tests measuring biological life in soil and water.

Official reports and expert analyses are visible in daily farmers’ lives, in fields, seasons, and accumulated losses. Zainab Mohammad, a farmer from Bazouriyeh, describes what they face amid neglect.

Farming Without Registration and the Closed Door

Zainab recounts returning to her land only to face compounded losses and near absence of support. “I have worked leased land for about eighteen years, paying one hundred dollars per dunum annually. I plant spinach, lettuce, and radishes in winter, and tobacco in summer as my primary income. After displacement, seeds were lost and seasons wasted. I managed only one season, with losses not less than ten thousand dollars. We healed from living flesh, yet more than a year has passed without assistance.”

She confirms agriculture is her only work. “Sale prices do not cover costs. Continuing requires harsh austerity. We have children and expenses. The biggest obstacle is administrative. They demand an agricultural registration that I cannot obtain because I farm leased land and the owner refuses to provide the property number. I am denied even minimal support, affecting our ability to rehabilitate the land.”

Environmental expert Dr. Sally Jaber explains the invisible impact of war on soil.

Environmental Coma

White phosphorus does not completely destroy soil, but it severely weakens it and can push it into a state comparable to environmental coma, reducing its capacity to sustain plant life until gradual recovery occurs with appropriate treatment.

Recovery is neither automatic nor quick. It requires partial and cumulative steps over many years, including removal of the most contaminated surface layers, a process that is time consuming, costly, and technically demanding. Improper treatment risks spreading contamination rather than containing it.

Shelling and rockets deposit chemical substances and heavy metals such as lead, mercury, cadmium, copper, and sometimes white phosphorus. These toxins interact with vital soil components, gradually poisoning them. Microorganisms essential to agricultural sustainability are harmed. Plants absorb pollutants through roots, threatening food safety and human health over time.

Shelling, fires, and the use of white phosphorus cause severe damage to mature trees.

Pollutants spread through wind and soil erosion from rain and irrigation, reaching deeper layers and expanding harm to surrounding soil, water, and air.

Jaber confirms that shelling and fires severely damage perennial trees. These trees do not die immediately, but their fruit bearing capacity declines over years, accompanied by harm to beneficial insects and reduced soil biodiversity.

Farmers’ displacement exacerbates damage due to absence of plowing, care, and monitoring, reducing fertility and allowing difficult problems to spread.

Biological treatment is helpful but insufficient alone. Chemical treatment is faster but more expensive. Certain plants such as clover and canola may absorb some heavy metals in long term programs. Testing irrigation water and artesian wells is essential because appearance and taste do not guarantee safety. Contaminated water can destroy an entire season.

Farmers’ stories reflect measurable scientific realities and risks. Wajeeha Hussein, a farmer from Bazouriyeh, recounts her experience.

“We Say Thank God and Continue”

Wajeeha Hussein, known as Umm Abbas, explains that their land was damaged due to a strike near neighbors. “We had an entire row of trees completely destroyed by shelling.” Citrus suffered less severe damage, and some trees were treated and stabilized and gradually improved.

Olives had been newly planted and were in their first fruiting year. Many saplings were destroyed and had to be replanted. Her sons planted more than five hundred saplings themselves. Some trees regrew after receiving water, prompting complete land renewal. “We turned the soil, plowed it, and planted again.” The family plans to plant chickpeas alongside olives and citrus and reserves small plots for beans, cabbage, and lettuce.

Losses are substantial. Olive land losses alone amount to about one thousand to eleven hundred dollars, in addition to nearby damaged plots. Her husband handles most agricultural work while her health prevents intensive labor. “We are both ill. My husband needs oxygen at night. But what can we do. We must live and try to continue.” They sometimes buy supplies on credit. Associations visited and documented damage, but nothing followed.

The family received no compensation for land loss, only a small amount for house damage. Still, she says, “We say thank God and continue.” Before the war, they were self sufficient and distributed olive oil within the family. This year they barely produced one container. “We planted again. What matters is that we are safe. Everything else can be replaced.”

Between daily loss and attempts to persist, the question remains beneath the soil: what did the war leave in the land, and what has not yet been tested.

The Gap in Testing and Transparency

Environmental journalist Mustafa Raad explains that to date it is impossible to confirm which metals settled in South Lebanon’s soil due to lack of transparency about collected samples and testing methods. Soil samples were gathered from about eight areas, with the Ministry of Environment working alongside the Ministry of Agriculture and the Earth Sciences Laboratory at the American University of Beirut. However, results have not been published, leaving the file incomplete.

White phosphorus fundamentally alters soil structure, turning arable soil into hardened ground resembling stone. A documented case from the 2006 war in the southern village of Kawkaba showed olive trees required five to six years to bear fruit again, meaning multiple lost seasons.

Soil recovery requires long periods. Technologies to remove phosphorus are extremely costly and cannot be applied widely, especially with approximately forty seven thousand olive trees burned, according to World Bank reports.

Farmers faced limited options this year. Olive and oil samples were taken and declared clean, yet mills were instructed to wash olives multiple times before pressing to reduce potential residues. Around seventy percent of the olive season was damaged, leaving only thirty percent of production. With one container requiring sixteen to twenty kilograms of olives, output declined sharply. Olive oil prices reached between 150 and 170 dollars in some cases, while some farmers sold at lower prices to salvage the season amid economic hardship.

Land Rehabilitation Is a Right

Bazouriyeh stands as a living example of what farmers in South Lebanon endure. The cost of war extends beyond immediate destruction to the land itself and to the farmer compelled to bear the burden of return to damaged soil that embodies identity and livelihood. Agriculture becomes an act of survival carried out amid insufficient protection and support, under cumulative losses unaccounted for in official recovery policies.

Serious action is required from the Ministry of Agriculture, municipalities, and relevant authorities in cooperation with experts to develop clear policies for rehabilitating damaged land, conducting necessary soil and water testing, and supporting farmers as the first line of defense for food security and the right to land. Without such intervention, the war continues, against livelihoods themselves and against the right to cultivate and to live.