A joint investigative report by Nourhan Sharafeddine and Ali Aouad.

The mobile phone is no longer just a tool for making calls – it has become a gateway to every detail of modern life. In today’s digital age, nearly everything we do, from studying and working to entertainment and communication, passes through a phone number that is now as essential as basic necessities.

But behind this seemingly simple act of owning a mobile line lies a tangled web of suspicion and security scrutiny in Lebanon -one that can drag ordinary citizens into interrogations over terrorism, espionage, theft, or even murder, simply because a number registered in their name was misused by someone else.

Alaa (a pseudonym) recounts how he once sold his mobile line to a friend who had hired two undocumented workers. Because they lacked identification papers, his friend bought two mobile lines under his own name so they could use them for work.

Although shop owners in Lebanon rarely register mobile lines in their own names for their employees, Alaa’s friend felt compelled to do so. Four months later, the two workers quit on the same day. Three months after that, security forces summoned him for questioning after discovering that one of the lines had been resold multiple times -ending up in the hands of individuals accused of terrorism. Suddenly, he found himself treated as a suspect simply because the number was registered under his name.

In Lebanon, a complex maze of suspicion and security procedures

can easily pull ordinary people into terrorism investigations -all because of a phone line

During interrogation, security forces showed the detainee photos the two workers had taken of people and locations, which they had later sent to other numbers. Only then did he realize the images were part of preparations for terrorist activity -and since the lines were registered under his name, he was the one summoned for questioning.

According to Alaa, his friend managed to prove that the workers had resigned, using documented WhatsApp conversations and security camera footage from the shop showing their presence during working hours. After the investigation, he was released only after signing a pledge promising never to sell phone lines to people without identification, formally distancing himself from the two numbers and placing full responsibility on the former employees.

Beaten and Tortured Over a Phone Call

Samir (a pseudonym), a Syrian young man who lived in Lebanon since 2010, says:

“I own a shop that sells phones and SIM cards, so I constantly receive calls from numbers I don’t recognize. I have to answer – it could be a customer, and I can’t afford to lose clients. One day, I received a call from an unknown number while I was busy and couldn’t pick up. The caller tried again later, so I answered and spoke for only 16 seconds. Shortly after, security forces arrested me because that number was linked to international theft cases.”

Samir continues:

“I was arrested and spent 15 days in detention. I was beaten and interrogated over a crime I knew nothing about, before being deported back to Syria. Those 15 days were the hardest of my life. I had been living legally in Lebanon for years, I had a stable job and my own shop – but one incoming call on my phone, with no wrongdoing from my side, ended with me being deported.”

People in Lebanon are not only questioned over international crimes – even calls linked to local criminal cases can lead to arrests and interrogations.

‘My neighbor owned a phone shop and called one of his suppliers to ask about an order,’ says Majed (a pseudonym). ‘A few hours later, security forces raided his house at night and arrested him. He spent about ten days in the Ministry of Defense and was tortured during interrogation. Eventually, it turned out that the person he had called was murdered, and my neighbor’s number was among the last three to contact him.’”

Majed adds:

“He came out a different person. He shut down his shop and stopped selling mobile lines. He now runs a small store that sells cassettes instead.”

I spent 15 days in detention,

beaten, tortured, and interrogated over something I knew nothing about.

These cases reveal an even darker side of the issue: the suffering doesn’t stop at interrogation or investigation – in many cases, it extends to physical torture. The case of Ziad Itani is one of the most prominent examples, and the death of the Syrian young man Bashar Abdel-Saoud under torture in a State Security center remains another painful reminder.

Lawyer Mohammad Sablouh confirms that several detainees in cases involving mobile numbers were beaten or mistreated to force confessions. He adds that torture is still used as a pressure tactic during investigations, noting that some of his clients signed confessions under torture. Refugees, he emphasizes, are often the most vulnerable – targeted simply because they purchased lines irregularly, even when they have no connection whatsoever to the crimes under investigation.

Despite Lebanon having passed a law in 2017 criminalizing torture, human rights activists say the practice remains widespread in several detention centers. As a result, unclear or faulty telecom records often lead to human tragedies, where innocent people pay the price of nothing more than a phone number.

Wadih Al-Asmar, head of the Lebanese Center for Human Rights, explains:

“Law 65/2017 criminalizes torture in detention centers, yet torture is still used as an interrogation tool in Lebanon. Whether suspects or witnesses, people are tortured, and judges continue to accept confessions extracted under torture. Most detainees experience torture — especially those accused of terrorism. Torture usually happens during interrogation, and almost every security agency participates in it. Direct torture inside prisons is less common; ill-treatment during investigations is more widespread.

An Unlimited Number of Lines Registered Under a Single Identity

According to sources at the Ministry of Telecommunications, around 5,158,136 mobile lines are currently active in Lebanon, based on the annual operational average over a 12-month period.

Data also shows that around 1,018,000 new lines are added to the market every year, based on the average of the past three years.

In contrast, approximately 922,000 lines are canceled annually, based on average cancellation statistics from the last three years.

Despite the simplicity of the requirement for owning a mobile line – a valid ID – this document becomes an existential obstacle for many. This includes refugees without passports or legal residency, people who entered Lebanon through illegal crossings, stateless individuals, workers whose employers confiscate their passports, displaced people unable to renew residency and forced to use expired papers, or minors under 18 who cannot legally obtain lines.

Even though ID requirements seem simple…

for many who lack identification, this requirement becomes a life-altering barrier

Telecom Ministry sources explain that Lebanese citizens register mobile lines using an ID or passport. For non-Lebanese, a passport with a valid visa or residency stamp is required. Syrians must provide an ID along with valid residency. Lebanese military personnel, Syrian refugees, and Palestinian residents each have specific identification cards required for line registration.

However, a person can still purchase a line on behalf of someone else. Mona (a pseudonym) explains:

“I bought a line for my husband using my ID. We went to an Ogero center and submitted my ID. We waited three hours to get the line, and because my husband had work, I completed the process instead of him. We chose Ogero because prices in regular shops were four times higher.”

The Ministry of Telecommunications confirms that subscribers may purchase up to eight prepaid lines at company branches, and up to two lines at private retail points. Landlines have no limit, while “special” or “premium” numbers have a maximum of five per customer, depending on their category.

In practice, this allows individuals to own large numbers of lines, even though the Ministry prohibits selling SIM cards without verifying identity. But the ban did little to stop the rise of a black market. Ministry sources admit that some numbers are sold illegally without confirming the identity of new owners, especially since many of these lines were initially activated using a valid ID from previous buyers.

20% of Mobile Lines Are “Illegal”

Security sources reveal that the core problem lies in how unsold SIM cards are treated as “dead stock.” To avoid financial losses, shop owners register them using any available identity — even if unrelated to the buyer. These cases make up nearly 20% of all mobile lines in Lebanon, meaning one out of every five lines is registered under someone who doesn’t actually own it.

Security sources add:

“Mobile lines are issued by the Ministry of Telecommunications through the two cellular companies. They are sold to primary distributors who supply small shop owners. If a line is not sold, distributors register it under any identity to avoid losing money. We cannot restrict this practice because it would cause massive financial losses and burden small shops and distributors.”

Mobile lines are funneled from the Ministry of Telecommunications, through the two cellular operators,

then distributed to major wholesalers and ultimately to small mobile shops across the country.

The risk of unregulated line registration goes far beyond legal or security concerns – it threatens digital safety. A person’s digital identity in Lebanon is directly tied to their phone number, used for bank accounts, social media, work applications, and secure communication. When a number is sold or registered under someone else’s name, the original user’s data, messages, and photos become vulnerable to hacking, blackmail, or criminal misuse without their knowledge.

Abed Qattaya, director of the Media Program and Internet Governance Project at SMEX, says:

“A phone number is now the primary key to a person’s digital identity. Selling or transferring it without safeguards is a major violation of digital security. It allows access to WhatsApp, Telegram, and even online banking services.”

He adds that companies still sell SIM cards without proper identification — something that must stop, and both companies and the Ministry should be held accountable for protecting users’ data.**

And with weak digital awareness among many users – who don’t realize that lines they register or resell may later be used for spying, fraud, or hacking – a national awareness campaign must accompany any reforms to SIM card registration procedures.

Tracking Mobile Lines as a Tool for Justice

Despite the concerns surrounding line registration, the system remains essential for solving security cases. The Ministry of Telecommunications works with security and judicial authorities, as well as the two cellular companies, to uncover crimes that shake the country.

This was the case in the 2011 “Taxi Killer” incident: the murderer discarded the SIM card he used on the roadside, where a young man found it and began using it. Through that line, investigators were able to trace the real killers after questioning the person who found the SIM card.

Security sources also told Sillat Wassel that similar methods were used after the 2007 Nahr al-Bared battle, where authorities tracked the phone lines of collaborators involved in the conflict. The army arrested them and uncovered others across Lebanon through mobile data.

The Ministry of Telecommunications explains the official mechanism:

“Security and judicial agencies cannot request mobile data verbally or directly. They must obtain an official judicial authorization — a court order or written warrant – issued by the Public Prosecutor, an Investigating Judge, or a competent court.”

“This authorization is sent to us and clearly identifies the type of data required. We respond immediately and provide the information exclusively to the requesting authority, and strictly within the scope defined by the court order.”

The Ministry adds that coordination happens strictly within the legal framework, and only through the ministry, with technical teams providing the data after receiving judicial authorization.

However, the real danger lies not in accessing crime-related information – but in extracting false confessions from innocent people under torture, or in wrongfully prosecuting citizens simply because they once owned a SIM card.

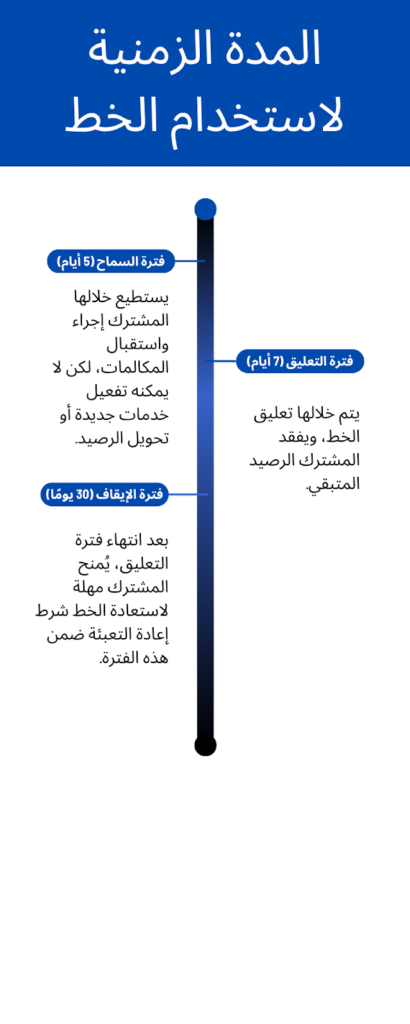

Another problem emerges when people buy SIM cards from the black market or resell them shortly after purchase. For prepaid lines, when the top-up deadline passes, the following timeline applies:

Grace Period (5 Days): The subscriber can make and receive calls, but cannot activate new services or transfer credit.

Suspension Period (7 Days): The line is suspended and any remaining credit is lost.

Deactivation Period (30 Days): After suspension, the subscriber has one month to reactivate the line by topping it up.

The Ministry explains that if the subscriber does not top up during the deactivation period, the line may be reissued and resold. Each SIM card type follows a different lifecycle depending on its category.

This raises a critical question: what happens to people who fled war without documents, and who have no legal pathway to owning a mobile line under current regulations?

In many cases, people whose lines expired find themselves in an even worse situation. When they call the telecom companies to retrieve their number, they are told it has already been resold, and they must personally contact the new owner to negotiate its return.

One example is a carpenter known among clients by his long-standing phone number. After losing the line, he was forced to buy it back from another person at double the price – just to preserve his livelihood.

In other cases, new line holders try to coordinate with telecom shops before the number is returned to the market, especially if they personally know the previous owner. But most attempts fail because shop owners refuse to intervene, fearing legal repercussions over how the line may have been used. Their standard reply: “It’s not our responsibility. Try to get your number back yourself.”

The Cabinet Renews Its Authorization for Security Agencies to Access Telecom Data Twice a Year

Security sources reveal that although SIM registration used to be a major concern for the judiciary, coordination has improved. Security agencies no longer need to interrogate every person who ever used a line – thanks to direct monitoring conducted with the help of telecom companies, enabling investigators to narrow down suspects.

While this development speeds up investigations and reduces the number of people questioned, it also opens the door to broader and quieter surveillance, where citizens may find themselves monitored without ever knowing.

Abed Qattaya explains:

“The Cabinet renews the security agencies’ mandate to access telecom data twice a year. This has been the case since 2011, when telecom data was first handed over in the context of Lebanon’s support for the Special Tribunal for the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.”

He adds:

“Security forces can also request data from internet service providers. Obtaining this information requires judicial authorization, which is not difficult – and is common worldwide under what is known as Legal Intercept. The concern is that sometimes more data is requested than what is truly necessary for security purposes.”