The moment you step into Laila Soueif’s home, it looks at first like any other grandmother’s house — old chairs, worn-out walls, and a few relatively new pieces of furniture that have found their way in over the years. In one corner, you notice a framed picture: a striking phrase set against the image of a young man in his prime. You sense it is the son of the house’s owner, but the words force you to pause, trying to process what really happens here: “If all you have is your body, how will you rise up with it?”

You realize this house resembles other grandmothers’ homes only on the surface. A grandmother’s house is usually warm, filled with the laughter of children, endless food with no start or finish. They are the safest places on earth — where joy fills the walls, a refuge for adults seeking shelter from life’s hardships, and a playground for children free from parental rules. But this house has no part in that world.

You realize this house resembles other grandmothers’ homes only on the surface. A grandmother’s house is usually warm, filled with the laughter of children, endless food with no start or finish.

Here, the walls scream in silence, and gloom hovers like a winter cloud. In this home, all seasons are winter. There is no food, because the homeowner has been on hunger strike for more than 242 days. The family has not been together for over six years, as the grandmother’s son is imprisoned in cases surrounded by questions and doubt.

After serving his sentence and with the family expecting his legal release around eight months ago — specifically in September 2024 — Laila was shocked to find that her son’s imprisonment had been extended, with the pretrial detention period not counted toward his sentence. This directly contradicts Egyptian law, as Article 482 of the Egyptian Code of Criminal Procedure stipulates that “the duration of a custodial sentence begins from the date of arrest of the convicted person, with a deduction for periods spent in pretrial detention and in custody.”

This disregard for his pretrial detention years was justified on the grounds that his investigation in a previous case — for which he had already been held in pretrial detention — was considered separate from the case on which he was ultimately convicted.

The story of Laila and her son, Egyptian human rights activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah, began with a series of arrests that led to a five-year prison sentence — though it now appears he will serve seven, if it ends there at all. His most recent arrest was in 2019, during a wide-scale crackdown, when Alaa was accused of sharing a post about the death of a detainee. He was prosecuted on charges of spreading false news via a social media platform.

The story of Laila and her son, Egyptian human rights activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah, began with a series of arrests that led to a five-year prison sentence — and it is clear he will end up serving seven, if it stops there at all.

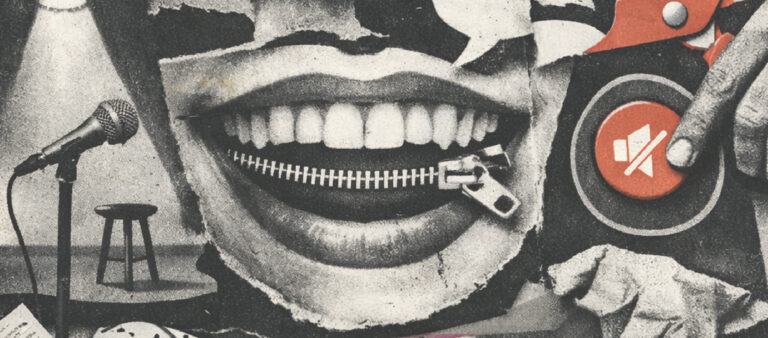

It was here that the spark for Laila’s hunger strike was lit — a strike that lasted more than 242 days. By that time, she and the rest of Alaa’s family, along with the campaigners working for his release, had exhausted every possible means to free him. She realized that the only weapon left to defend her son was her own body, and she resolved to “starve so he may live.”

Laila’s hunger strike unfolded in several stages. From the beginning until February 2025, she carried it out at home. Eventually, she had to go to the hospital to continue. By then, news of her strike had reached Alaa in prison, prompting him to join the strike as well. Laila then eased her protest slightly, consuming about 300 calories a day through a liquid nutritional supplement. But by the end of April, she had returned to a full hunger strike once again.

As of the time of writing this article in late May/June, Laila had once again been moved to the hospital, fighting for her life with a blood glucose level of 8 mg per 100 cm³ — far below the normal range of 70 to 99 mg per 100 cm³. This leaves us unsure, by the time this article is published, whether we will be adding a final note to mourn Laila or to congratulate her on her perseverance — though sadly, the latter feels almost impossible.

I dislike this tone of pessimism, one that Laila herself never taught us. In her last recorded interview on Al-Manassa, she said:

“Solidarity from different groups is the most important thing that helps one mentally accept what’s happening and be able to keep going.”

So, Laila, I take back my words. I place my hope — my wager — that one day the postscript to this article will be a congratulation, not just to you but to all of us, on Alaa’s release. And I will place another hope: that all prisoners of conscience in our region, women and men alike, will one day be free. Though I must admit, my hope for the latter is much smaller than my hope for Alaa’s freedom.