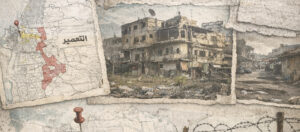

The Israeli enemy has not only destroyed thousands of homes in South Lebanon, displacing hundreds of thousands of people and turning the areas bordering occupied Palestine into uninhabitable zones, but it has also issued a warning banning fishermen from sailing between Ras al-Naqoura and the Awali River, depriving them of their livelihood.

As if the fishermen’s daily struggles were not enough—grappling for years with economic collapse and people’s declining ability to buy fresh fish—the latest developments have pushed them further to the margins, leaving them to face yet another dimension of the country’s crisis alone.

Following the Israeli warning, Lebanon’s security authorities and the Port Directorate informed the Fishermen’s Syndicate of a decision to halt fishing activities for the fishermen’s own safety. The Syndicate in turn relayed the order to all fishermen. The harbor quickly turned into a parking lot for idle boats, while the main fish market (al-Miri) was forced to shut down.

Fishermen Relocate Their Boats from Saida Port to North of the Awali River

But on Saturday, October 19, 2024, the Syndicate was informed by the Lebanese Army’s intelligence branch that fishermen were not banned from sailing. Accepting such a ban, the army noted, would imply recognition of the Israeli warning. Fishermen could therefore resume work—but entirely at their own risk.

In response, the Fishermen’s Syndicate in Saida issued a statement on Sunday evening, October 20, 2024, addressed to its members.

“Dear fellow fishermen,

Greetings,

Yesterday we were informed by the Lebanese Army’s intelligence services that fishermen are not prohibited from going out to sea and that they do not endorse the Israeli enemy’s warning. Therefore, anyone wishing to sail may do so. However, given the current circumstances, each fisherman must bear full responsibility for his own actions.”

The Syndicate therefore considers that fishermen are free to make their own choices, with each one fully responsible for his own decision.

The statement went on:

“Since the warning came from the Israeli enemy—an entity that can never be trusted—we urge our fellow fishermen to be cautious when making their decisions. The Syndicate will hold several rounds of consultations in the coming two days to seek appropriate solutions for the fishermen.”

The Syndicate also announced that on Monday, October 21, 2024, it would meet with MPs and community leaders in the city to determine the proper course of action.

The Fishermen’s Syndicate

Mohammad al-Samra, Secretary of the Fishermen’s Syndicate in Saida, explained:

“Around 350 people working in this sector—from boat owners to crew members—have been forced to stop working. The closure of the main fish market (al-Miri) has also left around 80 others without jobs, including fish sellers and workers responsible for cleaning and preparing the catch. All of them depend on daily earnings. This shutdown has effectively cut off their only source of income and left their families without a means of survival.”

The exact size of Saida’s daily fish production is unknown. One fisherman, A.B., explained: “The daily catch usually ranges between 100 and 400 kilograms, depending on the weather and what the sea provides.”

According to the Fishermen’s Syndicate, around 350 people working in this sector—including boat owners and their crews—have been forced to stop working. The closure of the main fish market (al-Miri) has also left around 80 additional workers jobless, from fish sellers to cleaners and processors. For all of them, it means a sudden loss of income and the collapse of their only means of survival.

On the question of livelihood, one fisherman put it bluntly: “I no longer care about how much I get from the sea to feed my family. What worries me is whether I can afford the cost of my medicine—something I can’t even secure from charities anymore.”

Another fisherman, Z.S., sitting in a café and smoking his waterpipe, added: “I don’t know what to do at the end of the month. I have to pay $200 in rent. How am I supposed to secure that amount when the sea is closed to us and no one cares about our plight?”

Steps Taken

To address the worsening situation, Syndicate head Mohammad Bouji met with MP Dr. Abdul Rahman Bizri to outline the fishermen’s hardships. The Syndicate also visited MP Dr. Osama Saad, who in turn raised the issue with Public Works Minister Ali Hamieh. According to Hamieh, international coordination had allowed commercial ships to continue operating, and he was seeking ways to reach a solution for the fishermen as well.

The Syndicate further approached the Hariri Foundation, where an official asked fishermen to fill out a government form designed primarily for displaced persons in order to apply for aid.

A source in Saida Municipality confirmed that the city’s crisis unit would attempt to allocate part of the available assistance for fishermen. However, he admitted: “Given the current circumstances, the municipality itself cannot offer any direct aid, since all our limited resources are already directed toward displaced families.”

Syndicate Secretary Mohammad al-Samra voiced frustration: “Neither central nor local authorities have shown any concern for us. All we ask is that the relevant bodies accelerate the delivery of humanitarian aid to this collapsing sector, so fishermen can cope with daily living costs and secure medicines for those suffering from chronic illnesses.”

He stressed again: “No one in authority—neither central nor local—has cared about us. What we demand is swift humanitarian assistance for a vital economic sector on the brink of collapse because of the war.”

An activist from the Raise Your Voice coalition was equally critical of the authorities’ silence: “Where is the Ministry of Social Affairs and its programs to support these vulnerable groups? Where is the Higher Relief Commission to assist workers in this productive sector who have lost their only source of income because of the ongoing war? Where are the authorities at every level, and why are they not shouldering their responsibilities toward their own citizens?”

History itself offers a reminder: in 1975, Saida’s leader, Maarouf Saad, was martyred while leading a fishermen’s protest in defense of their livelihoods. Nearly half a century later, the same fishermen find themselves asking: What now?