The Impact of the War on Gaza after October 7 on Egyptian Women’s Reproductive Choices: Between Emotional Solidarity and Social Shifts

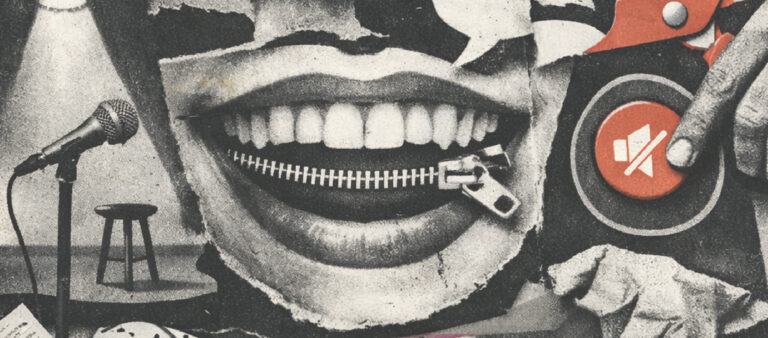

In times of war, it is not only cities that are bombed, but the very trust in life itself. The destruction goes beyond the walls of homes to strike at something deeper: the meaning of existence, the continuation of generations, and the future of children yet to be born. From the repeated scenes in Gaza, a profound question rises to the surface: Is it ethical to bring children into a collapsing world?

In the wake of the latest war on Gaza, an increasing number of women’s voices are signaling a noticeable shift toward the choice of non-reproduction—not as an act of selfishness or individualism, but as a psychological, and perhaps even spiritual, response to a shared, profound experience of pain, helplessness, and fear of seeing tragedy repeated in a new generation.

This phenomenon, which at first glance might seem merely a reflection of trauma, warrants deeper examination: What compels a 25-year-old woman to say, “I will not give birth to a child who might be buried beneath the rubble of a house I cannot protect”? How does psychiatry view such decisions? And can society acknowledge that rejecting reproduction during wartime is not always an escape from responsibility, but sometimes its highest form?

In the wake of the latest war on Gaza, an increasing number of women’s voices are signaling a noticeable shift toward the choice of non-reproduction—not as an act of selfishness or individualism, but as a psychological, and perhaps even spiritual, response to a shared, profound experience of pain.

In this report, we weave together contemporary psychological insights, statistical analysis, and first-hand accounts from Egyptian women who have either lived through war or witnessed it closely, to outline the contours of a growing tendency: non-reproduction as a conscious act in the face of a world that imposes suffering and criminalizes caution.

Modern psychiatry emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between a decision not to have children that is based on stable awareness and personal planning, and one that emerges from acute psychological trauma. While the former is in no way considered pathological, the latter—especially when stemming from war-related anxiety disorders or depression—calls for psychological support, not moral judgment or social blame. This aligns with the DSM-5, which notes that exposure to trauma—such as war—can increase the likelihood of conditions like PTSD and generalized anxiety disorder, both of which may affect a person’s ability to make long-term life decisions.

Gaza had over 50,000 pregnant women at the outbreak of the war, many of whom gave birth under catastrophic conditions—amid bombardment, power outages, and severe medicine shortages.

According to UNFPA reports, Gaza had over 50,000 pregnant women when the war began, many of whom gave birth under catastrophic conditions—amid airstrikes, power outages, and severe medicine shortages. At Al-Shifa Hospital, Gaza’s largest, harrowing scenes unfolded as women delivered without anesthesia or adequate equipment, and some infants were born orphans after their mothers were killed during childbirth.

Voices from Within: How Individual Convictions Took Shape After the War

Amid rubble and bombardment, and under the relentless images of children pulled from beneath the debris, a growing number of women have formed deep convictions against reproduction—not as a passing reaction or temporary stance, but as the outcome of an intense, shattering emotional experience that calls the very meaning of life into question.

Aya Sabry, a 25-year-old Egyptian woman, describes her shift from economic non-reproduction to moral and existential non-reproduction. She says: “I had been thinking about not having children for a long time, for economic reasons and fear of responsibility. But after the war, it became a decision. I’m not ready to bring a child into this world, knowing there’s even the slightest chance they could experience the worst. I’m not willing to create someone who might suffer, even if they grow up loving the cause.”

For Asmaa Bakhit, 30, who gave birth to her first child two months before the war, motherhood was initially filled with joy. But the war changed everything. She says: “After seeing what happened at Al-Ma’madani Hospital, everything inside me shifted. It wasn’t just fear for my son, but the feeling that I could never go through this experience again. The targeting of children made me realize that having children is not just a personal choice—it’s also a psychological challenge I can’t bear.”

Hadir Mohamed has gone to the furthest depths of existential pain—not only rejecting reproduction, but expressing a deep-seated wish never to have existed at all, because of the injustice and brutality she has witnessed. She says:

“Every time I see a child now, I feel pity for them. My feelings about life itself have changed. Those who truly love their children wouldn’t bring them into all this. This war made me wish I had never been born.”

In contrast to this rejection, Yousra offers an alternative vision based on fostering and adoption. She does not reject motherhood, but refuses to “produce” a new child into a dangerous world. She says:

“I’m for the idea of fostering; I don’t have to bring a child from my own body. There are many children who need a safe home. After the war, I’ve felt more strongly that the most important thing we can offer is not new life, but a safe life for those who already exist.”

In this context, Dr. Gamal Fawrez, a consultant psychiatrist, notes that some of these positions may stem from an “obsessive” personality type prone to over-planning and excessive fear of the future, which can lead to an inflated sense of potential danger. Such individuals may interpret scenes of war in catastrophizing ways that go beyond reality, causing their psychological resilience to collapse and pushing them toward extreme existential decisions, such as rejecting reproduction altogether.

This intersects with what is found in modern psychological literature, such as the DSM-5, which indicates that exposure to trauma—like wars—can increase the likelihood of disorders such as PTSD and generalized anxiety disorder, both of which affect people’s ability to make long-term decisions.

What we are witnessing is not merely an individual psychological disorder, but a cultural shift tied to loss of trust in systems, the absence of safety, and a growing sense of helplessness in the face of injustice—all of which are laying the groundwork for a new non-reproductive culture.

He adds: “This way of thinking is not entirely wrong, but it reflects a distorted reading of the future. Even in the worst crises, we cannot project inevitable danger onto all times and places. A neurotic mind amplifies pain and always expects the worst.”

We can expand on Dr. Fawrez’s analysis to understand how these decisions intersect with broader transformations in collective consciousness.

What we are witnessing is not merely an individual psychological disorder, but a cultural shift tied to loss of trust in institutions, the absence of safety, and a growing sense of helplessness in the face of injustice—all factors that lay the foundation for a new non-reproductive culture.

This refusal, then, is not simply an emotional reaction or an escape from responsibility, but a symbolic act of protest—an act of withdrawal from a system perceived as either incapable of, or hostile to, sustaining life itself.

Between Existential Anxiety and Collective Awareness: A Deeper Psychological Reading

Dr. Hagar Ramadan, a psychiatrist and addiction specialist, reinforces this perspective, noting that the growing tendency toward non-reproduction may be linked to what is known as “existential anxiety.” She explains:

“When I don’t feel safe in this world, the idea of having a child becomes anxiety-inducing. How would I raise them? What if they were harmed?”

She adds: “These feelings intensify in weaker, more fragile societies—those plagued by violence, corruption, and instability—conditions that amplify insecurity and increase hesitation about having children.”

She highlights a key distinction between a decision that stems from awareness and insight, and one driven by trauma or momentary emotional upheaval:

“Sometimes the decision not to have children is the result of psychological trauma, and sometimes it comes from deep awareness and logical thinking. The difference lies in the nature of the decision itself—whether it is calm and balanced, or sharp and impulsive.”

“A conscious decision to reject reproduction can at times be a natural response, especially when based on a logical assessment of surrounding circumstances, whereas an impulsive decision may signal a disorder that needs care.”

She continues: “People respond differently to disasters. Some personalities are highly sensitive to traumatic experiences—especially those with high levels of empathy—who feel the suffering of others as if it were their own, making them more vulnerable to psychological disruption in the face of catastrophes.”

A conscious decision to reject reproduction can at times be a natural response, especially when based on a logical assessment of surrounding circumstances, whereas an impulsive decision may signal a disorder that needs care.

She notes that people with a strong sense of responsibility, or those who grew up in unstable families, are more likely to consider non-reproduction:

“Those with a heightened sense of responsibility may feel they cannot bring a child into an unsafe world, or believe they are unfit because they themselves never experienced a stable family model. And in societies lacking real support for women, these fears are magnified.”

She concludes: “In societies with higher levels of education and stronger support systems for women, we find a greater awareness of the world’s harsh realities, and reproductive decisions are made with deeper reflection—sometimes becoming a form of conscious resistance.”

Between Motherhood and Protest

“In a world that never stops bombing, motherhood becomes an exhausting act of courage, and giving birth is not an extension of life but a gamble with death. Between a child born in a tunnel and another pulled from beneath the rubble, women today face not only the question, ‘Should I have children?’ but a deeper one: ‘Does this world even deserve to welcome a new soul?’”