The decision to be childfree is never a calm one when women make it. When the feminist writer and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir announced that she did not wish to have children, her choice was neither an act of rebellion nor a rejection of motherhood. Rather, it was a decision rooted in freedom and outside the normative roles imposed on women. Yet this decision did not escape the circle of social suspicion—neither for Beauvoir nor for the many women who came after her.

The central question here is: why are women constantly questioned about their reproductive choices, while any decision outside this framework is treated as an exception? And why do women’s choices require justification or remorse, as if what they decide is a deviation from “nature” itself?

From early childhood, girls are forcibly introduced into maternal roles. The story begins with the very first toy handed to a little girl: “This is your baby-take care of her.” This toy is not innocent; it is early training for a socially acceptable female role. The girl quickly learns that childcare is the mother’s responsibility, as roles unfold in sequence: a “girl prepared to become a bride,” and a bride expected to become a mother as a “natural destiny.” She is told the decisive phrase: “Your end is marriage and motherhood.” Even if a woman earns the highest academic degrees, her education is often viewed merely as a path whose ultimate purpose is to raise her own children-reducing life to a single, inevitable ending with no alternatives.

In societies where girls are trained for motherhood from their earliest years and gender roles are strictly defined, how are women who choose not to pursue this path perceived? Rarely is this decision treated as a conscious choice; more often, it is framed as rebellion or deficiency.

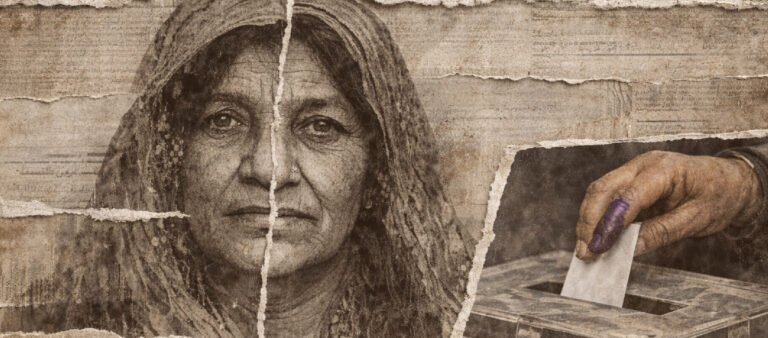

Who Holds Power Over Women’s Wombs?

In our societies-particularly in the East-girls grow up under the authority of the family and a patriarchal system that grants itself the right to use women’s bodies at will. It overlooks all forms of violence, yet tightly controls the womb, fertility, and the timing of childbirth. The woman’s body becomes a site of regulation and discipline, not a space of rights and choice.

Within this context, childfreedom is not confronted as a legitimate option, but as a departure from the social script that demands symbolic punishment: pity, doubt, unsolicited advice, or fear-mongering about regret. Women are socially sanctioned and repeatedly forced to justify their lives and choices.

Beyond Biology: Intersecting Visions of Beauvoir, Carroll, and El Saadawi

Philosophical and social perspectives converge in questioning one of the most deeply rooted assumptions in human consciousness: the inevitability of reproduction and the linking of women’s worth to bodily biology. This interrogation begins with its existential roots in Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, where she rejects the notion of motherhood as a woman’s ultimate fulfillment, instead treating it as a social and historical experience imposed under unequal conditions.

Beauvoir argues that “motherhood can only be a liberating experience if it arises from conscious choice, not as an imposed destiny.” Society transforms biological facts-pregnancy and childbirth-into moral obligations and existential missions, demanding that women find absolute meaning in them, even when the experience is exhausting or psychologically contradictory. Mothers often live a sharp divide between what they are expected to feel and what they actually feel, under a social taboo that forbids acknowledging this rupture.

Motherhood can only be a liberating experience if it comes from conscious choice, not as an imposed destiny.

Beauvoir further notes that women often enter motherhood driven by marital pressure, time anxiety, fear of stigma, or the illusion of fulfillment through a child. This tension between the image of “completion and happiness” and real feelings of fatigue or anger is considered, in her view, a “betrayal” of the idealized mother figure-prompting her broader project of dismantling motherhood as a social construct that binds women from an early age.

This deconstruction finds contemporary resonance in writer Laura Carroll in her book The Baby Matrix, which views childfreedom as a mirror exposing a cultural system that has sanctified reproduction for centuries. Carroll does not merely critique pressure; she dismantles the cruel implicit question society poses: “What will happen to you if you don’t have children?” She argues that the desire for motherhood may not always be free, but rather the result of social conditioning and fear of “missing out.” She highlights how dominant narratives amplify stories of regret among childfree women while completely silencing stories of women who regret motherhood or experience it as a burden—manufacturing the illusion that regret is inevitable only in the absence of children.

Carroll adds an institutional dimension: religion frames reproduction as duty, education reinforces parenthood as inevitable, and public policy rewards it as a marker of sacrifice. Meanwhile, the discourse of “instinct” is deployed as a ready-made explanation that erases the fact that biological capacity does not automatically translate into psychological desire or conscious choice.

In the Arab context, Nawal El Saadawi intersects with these arguments through a radical vision in Woman and Sex, redefining the female body as a fully autonomous human entity, entirely separate from “social destiny.” El Saadawi draws a precise distinction between the womb as a biological organ and reproductive function as a tool of control, asserting that confining women to this role is a historical strategy aimed at neutralizing their intellectual and productive potential and keeping them confined to the private sphere. She goes further than Beauvoir and Carroll by insisting that motherhood under coercion is not a sacred act, but rather “submission to flawed social programming.”

What unites these feminist pioneers is a call to “humanize reproduction”—to transform it from an automatic function into a responsible choice exercised by a conscious individual. El Saadawi concludes that true women’s liberation begins when women recognize that their value derives from their intellect and human contribution, asserting that “excellence in thought or work is the true birth of the self.” Thus, feminist discourse-from Beauvoir to Carroll to El Saadawi-converges on the necessity of reshaping education and concepts, freeing women from the confines of “the crib and the kitchen” toward broader human horizons beyond rigid binaries of right and wrong.

Is There Truly a Safe Space for Women to Speak?

My friend Alia tells me that when she informed her family of her decision to reject marriage and motherhood, they did not take her seriously. Her choice was not explicitly rejected; instead, it was met with doubt and a withdrawal of legitimacy. Her decision was treated as temporary: “Once the right person comes along, she’ll change her mind.”

My friend has never viewed her body as a reproductive tool, even if she were to choose marriage. For her, marriage—if it happens-would be a life partnership, not a compulsory gateway to motherhood. Rejecting childbirth was not a rejection of life, but a rejection of stereotyping that flattens the depth of human relationships into ready-made biological roles.

At the same time, she does not express this choice beyond her close circle. Like many women, she shelters behind the language of “fate and destiny” to avoid the exhausting labor of explanation in a society that grants itself authority over bodies and wombs. Her story is not an isolated case; it represents a broad group of women who choose silence about how they wish to live.

My friend never saw her body as a tool for childbirth, even if she chose marriage.

She envisioned marriage-if it occurred-as a life partnership.

All of this forms part of the psychological and symbolic violence embedded in many societies. These societies surround women with constant doubt and strip legitimacy from their decisions regarding their own bodies.

According to a 2024 study by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on sexual and reproductive health and rights, social expectations confine women to stereotypical roles such as motherhood and reproduction, operating as a form of symbolic violence. These expectations undermine women’s autonomy over their bodies-including decisions related to sexual and reproductive health-thereby violating their right to make free and responsible choices without discrimination or coercion.

Women who choose not to have children still face a long path toward dismantling the stereotypes surrounding them, amid a lack of genuine recognition of choices no less legitimate than motherhood-such as opting out of maternity, building lives outside marriage and reproduction, and defining relationships beyond prescribed templates.

Ultimately, the struggle is not merely about defending the choice of childfreedom, but about liberating the concept of “fulfillment” from the cage of biological function. Today, redefining women’s lives beyond what is labeled “natural” or “prescribed” has become a necessity. The real question we must ask is not: “What will happen to a woman if she does not give birth?” but rather: Who decided she was incomplete to begin with?