I never imagined that sharing my experience on TikTok to warn others would turn into an attack against me. All I wanted was to alert my peers to the dangers of riding alone in cars, especially with the increasing number of sexual harassment cases. But I was surprised that this trend was confined and specialized for women only and that I should ‘defend myself instead of crying on TikTok like women,’ as they told me.” This is how Moncef, a 15-year-old Algerian boy, tells his story, highlighting the societal stigma that males face when talking about their exposure to harassment.

This stigma is compounded by other testimonies that show the depth of the suffering and silence males endure, especially at a young age. Abdul Rahman, an 18-year-old Algerian, recounts his painful experience: “I was sexually harassed at the age of thirteen while riding the bus. A man touched me in sensitive areas, taking advantage of the crowd. I couldn’t express myself at that moment, and I didn’t tell my family or friends what happened.”

Algeria suffers from an almost complete lack of an integrated system to support male and female child victims of sexual violence.

In a similar context, Mohammed, 30, offers a testimony no less painful: “I was harassed when I was ten years old. I was riding the bus, and an old man sat next to me. He started touching me, and I felt extremely scared. I couldn’t do anything, and I didn’t tell any of my family or friends for fear of blame or disbelief.”

Women have long been highlighted as the primary victims of sexual harassment, but is that the whole picture? Coinciding with the “Expose the Harasser” campaign launched by Algerian feminists in early May 2025, which encouraged many women to break the silence and share their video testimonies about harassment in public places, other stories began to emerge.

This campaign was not limited to empowering women; it also encouraged children to reveal their painful experiences, showing that this phenomenon is more widespread and complex than we imagine.

Between Legislation and Implementation: The Reality of Child Protection in Algeria

Abdel Raouf Abdi, a children’s rights activist and health communication graduate, explains that Algeria suffers from an almost complete absence of an integrated system to support male and female child victims of sexual violence. Despite the presence of some governmental institutions, they do not represent a comprehensive national system, and the associations that provide psychological and legal support suffer from a severe lack of funding and expertise. Abdi says: “Many families prefer to resort to associations instead of reporting to the police, due to fear of the complexities of the cumbersome security and judicial procedures.”

How can a child be asked to 'protect himself'? Can appearance or behavior be a justification for committing a crime of sexual harassment or rape?

Regarding the legal framework, Abdi adds to the Wasl platform that Algeria has a legal arsenal for the prevention and care of victims, such as the Penal Code and the Child Protection Law of 2015. However, he believes that the effectiveness of these laws has not yet been evaluated, and key mechanisms such as the national information system on child protection have not been activated, indicating a gap between legislation and implementation.

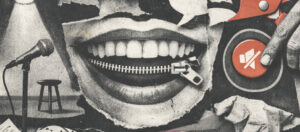

Regarding the media, Abdi believes that Algerian media outlets have shifted towards more professional coverage of issues related to violence against children by consulting with specialized experts. He stresses: “I warn against the danger of social media, where influencers have a significant impact, and their discourse is often superficial and carries implicit justifications for the assaults.”

When Platforms Become Mouthpieces for Victim Blaming

Algeria, specifically the state of Oran, was shaken last May 2025 after a video circulated on a local page showing an assault on a child, which sparked a wide wave of anger among the public and human rights circles.

What was alarming was the statement of a well-known Algerian rapper (name withheld for safety reasons), who posted, “Male child victims of rape are only effeminate children,” which sparked widespread controversy. This included hints that children were to blame for the assaults they were subjected to, which was considered a dangerous and implicit justification for such crimes.

This is not the first time this singer has made misogynistic statements that blame victims. A number of his followers supported his statements, raising painful questions: How can a child be asked to “protect himself”? Can appearance or behavior be a justification for committing a crime of sexual harassment or rape?

Such statements only make things worse, entrenching a culture of victim-blaming instead of holding the perpetrator accountable and providing the necessary protection for children.

In light of this reality, the question arises about the role of the Algerian “Audio-visual Regulation Authority” in issuing clear protocols and guidelines to ensure media coverage that respects the dignity of victims and serves the public interest, with a focus on including essential and sustainable training pathways for male and female journalists in this field.