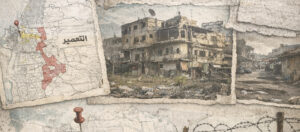

The conversation about thalassemia in the Palestinian community in Lebanon often centers on Burj Al-Shamali Camp, which hosts more than 180 cases among its residents. These cases are spread over an area of 134,600 square meters, with a total population of 19,600.

Wahid Wahid, responsible for the thalassemia file in the camp’s Popular Committee, monitors the cases and says: “The number of people affected is large, making up about 1% of the camp’s population according to the names we have registered. Women represent the majority, but the number of men is also rising since the disease is hereditary. Our camp lacks a specialized center for treating this illness.”

Thalassemia is not a new disease in the camp, but the difficult living conditions in the camps obstruct treatment and worsen suffering. The number of cases is notable, and in some instances, entire families are affected.

Although it is a form of hereditary anemia (hemoglobinopathy), thalassemia is not contagious. It causes a reduction in hemoglobin—the substance responsible for transporting oxygen throughout the body. The clinical severity varies greatly, ranging from mild cases without symptoms to severe or even life-threatening forms. One of the reasons for its prevalence in the camp is consanguineous marriage.

Dr. Mohammad Othman explains: “In the past, marriages were arranged without prior medical testing, and thus children were born with the disease—especially if both spouses were relatives carrying thalassemia traits. That’s why premarital laboratory tests are essential to ensure neither partner is a carrier. Unfortunately, some ignore this precaution. During pregnancy, it is also possible to test the fetus in the early months to determine whether it has the disease.”

A 2011 field study conducted by researchers—“Thalassemia Patients in Burj Al-Shamali Camp: Enormous Challenges and Limited Opportunities”—noted that if one of the couple is diagnosed with thalassemia, in-vitro fertilization (IVF) can help them have a healthy child.

One activist believes the key to addressing this problem in the camp lies in raising awareness about avoiding consanguineous marriages, especially among families carrying thalassemia traits, in addition to providing proper treatment for patients.

Double the Suffering

Nawal, a woman suffering from thalassemia, struggles financially, which prevents her from securing proper treatment and affording expensive medications.

Meanwhile, a young man named Yousef shared his story with Al-Ifada: “My illness was discovered in my early years. I used to undergo blood transfusions two to four times a month, in addition to taking medication regularly for the past ten years. The medicine costs 110,000 LBP, and my siblings help me get it since my health doesn’t allow me to work independently. I also need another drug that now costs 300,000 LBP per month.”

On top of this difficult situation, the bigger problem lies in the high cost of medication, which thalassemia patients must take daily depending on their condition. Around 53 severe cases require larger amounts of specialized medication to treat the disease.

Support Initiatives

The camp’s Popular Committee has been following up with patients and providing them with necessary support for the past six months, funded by a French organization. Many patients also receive “sporadic” support from foreign organizations such as the German association Tawasul and Doctors Without Borders, in addition to Palestinian local organizations like Al-Shifa Association.

UNRWA covers part of the medical assistance. Yet, as another patient summarized, the main issue remains: “Securing the essential drug for this disease—Hydrea, the most important medication in treating thalassemia. No organization provides it, and this adds to the harshness of treatment, especially financially, under these difficult economic circumstances.”

Fadi Ismail, one of the young volunteers in the camp, believes the most urgent need is to provide a doctor to follow up on the large number of patients in hospitals, conduct regular check-ups, and ensure necessary tests are carried out.

Doctors rely on two main tests to diagnose thalassemia: a Complete Blood Count (CBC) and specialized hemoglobin tests (Hemoglobin Electrophoresis).

These tests measure hemoglobin levels and examine different types of blood cells, such as red blood cells, in a blood sample. People with thalassemia have lower hemoglobin and fewer red blood cells than normal. Carriers of the disease, on the other hand, have smaller red blood cells than average.

The greatest challenge lies in properly interpreting laboratory results, since few labs provide accurate readings of the disease, and there is a shortage of qualified specialists capable of analyzing these results.