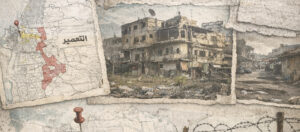

A harsh reality is imposed on thousands of displaced women who fled from the Shahba region to the Jazira areas of Syria following air and ground attacks carried out by the Syrian National Army and the Turkish occupation forces on December 1, 2024, targeting Shahba, which belongs to Aleppo city.

With essential sexual and reproductive healthcare services absent—services that should be treated as emergency priorities under responsible safety standards—these women face heightened risk. This is their second displacement, after first fleeing their hometown of Afrin, which only deepens their daily suffering and leaves them feeling powerless in the face of the harsh reality they are forced to endure, far from any real support or solutions.

A Real Dilemma

Berivan Bakr, one of the displaced women from Shahba, said:

“The suffering of displaced women in the displacement centers of Qamishli, in northeastern Syria, is worsening in the absence of the basic conditions needed for a healthy and safe life—especially in terms of reproductive and sexual health.”

She explained that even basic living needs—shelter, clean water, and healthy food—are lacking, which directly and negatively affects their personal hygiene and leaves them vulnerable to disease. On top of that, access to medical centers for women’s health issues is limited, particularly for conditions that require long-term treatment.

Bakr continued, describing the poor quality of services:

“When we turn to medical centers to manage our reproductive lives according to our dire living conditions—conditions that lack the most basic standards of physical, sexual, and psychological safety—we receive no medical support, and our hardships are not taken into account. We don’t even have the right to a loaf of bread for our children.”

No Sexual, Reproductive, or Mental Well-Being

Bakr told Silat Wassel:

“Our reality is bitter—especially since this is our second displacement. My husband, our four children, and I now live in Qamishli in a single room within a displacement complex. We cannot maintain a normal sexual life, which directly and negatively affects our marital relationship, leaving it unstable and at risk of falling apart. It lacks the basic elements needed to continue as any stable marriage should, with full freedom—but unfortunately, everything has changed for the worse.”

Sharing the same view, displaced woman Sabah pointed to “the shortcomings in community assistance, as well as the fact that the ruling authorities, humanitarian organizations, and NGOs in the area remain detached from our suffering. Our situation requires urgent sexual and reproductive healthcare services, but this is a subject that is difficult to discuss, even partially, and receives no attention whatsoever.

“For example, I was pregnant and needed regular checkups during my pregnancy—blood and urine tests, screenings for sexually transmitted diseases, and reproductive health monitoring—but I was not receiving any of these services. I had to travel to Aleppo, where my family lives, in order to give birth and get the necessary medical supplies for the delivery.”

We, the displaced women, suffer from the lack of safe medical abortion options in cases of unwanted pregnancy. This creates immense anxiety for us due to the poor economic situation, in addition to the shame we feel because of the stigma imposed on us by those around us.

Nazek, a 24-year-old displaced woman from Shahba, added:

“We displaced women lack access to safe medical abortion options in cases of unwanted pregnancy. This creates enormous anxiety for us, especially given the poor economic situation, and adds to the shame we feel because of the stigma from those around us. They make us feel as if our pregnancies are taboo, with constant insults. This poses a serious threat to our mental health, which is no less dire than the other aspects of our situation.”

Health Crises Without Treatment

“The injustices we face as displaced women—sexually and reproductively—are intensifying, creating psychological crises brought on by the displacement journey and by our very limited knowledge of these issues.”

“For example,” said Shireen (a pseudonym), a 23-year-old displaced woman, “I’ve faced serious challenges while suffering from severe vaginal infections, which caused complications that affected other parts of my body—one of which led to uterine fibrosis, likely requiring surgery in the near future. On top of that, there are no medical facilities or health centers that meet our needs, whether for medicines or medical staff to examine and treat us, even in routine cases.”

Shireen added:

“Displacement has already taken what was left of our spirits and broken our strength, but still, numerous obstacles stand in the way of getting solutions that meet our sexual and reproductive health needs through medical consultations. This happened to me when I developed vaginal dryness. I had no financial or medical means for treatment, and my physical disability also stood in the way of reaching health centers.”

Serious Consequences on All Levels

For her part, Dr. Khabat Mohammed, an obstetrician-gynecologist and surgeon, noted:

“There will be serious consequences—both in terms of general healthcare and in terms of mental, social, and economic well-being.”

The lack of care will lead to higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, hepatitis B, syphilis, and genital warts, which often progress to cervical cancer if not treated early. This is due to poor access to diagnostic and treatment services. It will also cause more cases of unwanted pregnancy due to the absence of family planning methods, and higher maternal mortality rates from the lack of proper care—especially in cases of postpartum hemorrhage, which require urgent attention. Added to this are psychological effects like anxiety and depression, and social effects such as lack of safety and protection.”

It is clear that the crisis is no longer limited to a lack of services; it has become an existential threat—a form of “clinical death” affecting bodies worn down by repeated displacement and systematic marginalization.

“As for pregnancy complications, there’s an increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, and bleeding during and after delivery. Neglect can also lead to preeclampsia or gestational diabetes. Poor nutrition among pregnant women affects their babies, causing complications that can be long-term. The shortage of medicines—such as those needed to treat anemia—further endangers mothers and can result in low birth weight in newborns.”

Is There Anyone to Help?

Dr. Khabat added, regarding the possibility of supporting displaced women and offering practical solutions:

“We can protect displaced women from the risks of lacking sexual and reproductive healthcare by providing basic health services—such as setting up mobile clinics, field health centers, and equipping highly qualified medical teams—while ensuring the availability of essential medicines and supplies, especially for pregnant women. This includes nutritional components and vitamins like iron. Reproductive health services should also be provided, such as distributing family planning methods to prevent unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions. In addition, mental health awareness is essential to protect them from problems related to violence, anxiety, and stress.”

Looking at the reality of displaced women in Qamishli and the multiple violations affecting their health, reproductive rights, and psychological well-being, it is clear that the crisis is no longer just about a shortage of services. It has become an existential threat—a form of “clinical death” afflicting bodies exhausted by repeated displacement and systematic marginalization. In this harsh context, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive humanitarian response that restores to women the minimum of their health and social dignity, and grants them the right to a normal, safe life—free from fear, deprivation, and exclusion.