When I picture Ziad Rahbani apart from his fruitful artistic life, and apart from being part of one of the greatest artistic families in the Arab world, I see him as that old man who never leaves the neighborhood—never letting a passerby escape his tongue.

No woman walks by without receiving his playful compliments, and no child fails to dodge him with odd excuses. His voice is louder than the neighborhood’s noise—in fact, it is the neighborhood’s noise.

And yet, no one minds. The children don’t dislike him, and the women don’t take his flirtation as harassment. Everyone loves him—young and old alike—and respects him despite everything. He fears no outburst in the face of injustice, and no one, no matter how important, dares to dismiss his judgment.

When he dies, the neighborhood will never be the same. And that is exactly what the artist Ziad Rahbani was in reality: when he passed away, the world could never be the same again.

Ziad inherited his name from a legendary artistic family—just mentioning “Fairuz” is enough to grasp the scale of the challenge.

Yet his voice never dissolved into the shadows of that family. Instead, he carved out his own presence with ease and sincerity. He wasn’t merely a continuation, but a standalone pillar who influenced everyone— even his mother’s own career. Many songs performed by Fairuz were, in truth, infused with Ziad’s spirit and essence. “Kifak Inta”, for example, unmistakably bears his fingerprint; it is more his than hers.

Many songs performed by Fairuz

were, in fact, Ziad in spirit and substance.

When we sing “El Bosta”, we’re not just singing a cheerful tune or a playful story about a girl named Alia—we’re singing for all our women.

I’ve never sung it to my beloved and thought of the real Alia. Her name never bothered us, because the song belongs to us; we rewrite it each time according to the one we love.

It’s the same with “Bala Wala Shi”: if you haven’t shared it with the one you love, you might want to rethink the relationship.

That’s Ziad’s magic—turning the deeply personal into something universal, and the universal into something deeply intimate.

Despite his seemingly sharp demeanor and perpetual short temper—as he once said of himself, “I’ve got a short fuse, and so does he”—his irritation was never directed at people or at life’s possibilities, but at injustice itself.

He was angry because the world wasn’t as it should be.

He wasn’t a mere pessimist, but an artist who saw more than the rest of us. That burning anger made his presence unforgettable, and his departure a loud tolling bell echoed across people’s pages and social media posts.

In the moment of farewell, everyone was united in their loss—because he was more than an artist; he was a voice for us all.

My personal connection with Ziad began late, when I stumbled upon a line of his in a recording: “Every time you ask me how I am, I’m reminded that I’m not okay.”

That phrase became my doorway into his radio program “Al Aql Zeena” (Wisdom Is a Blessing).

I hadn’t seen it during its original broadcast—perhaps I was too young. But I found in it a refuge: long sessions of listening, words that sparked wonder, endless questions, and, at times, an admission—“I don’t understand everything, because of the Lebanese dialect”—yet the feeling? Always there.

My friend Valentine Nassar shares this sentiment. She says:

“At first, I didn’t understand a word Ziad was saying—I was far too young. But Ziad was always present in our home. My father was passionate about him, and about Fairuz. I inherited his rebellious spirit, especially through (Al Aql Zeena) and plays like (An American Long Film) and (As for Tomorrow, What?). Ziad has this uncanny ability to read the future and unpack the complexities of Lebanese reality with both lightness and depth—and to me, that’s genius.”

Ziad has an uncanny ability to foresee the future and to unpack the complexities of Lebanese reality with both lightness and depth—and that is pure genius.

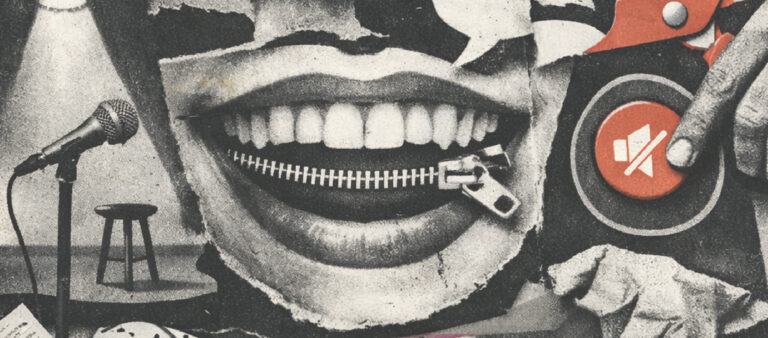

In everything he did, Ziad revealed us to ourselves—our own inner struggles.

He showed us that art is not a luxury, but a form of resistance. That a joke can be a weapon, and that love itself can be a political stance.

He left behind a legacy not only in melodies, but in ideas, in voice, and in the very way we see the world.

That’s why I’ll end my article with the line of his that never stops haunting me:

“Honestly, between you and understanding, there’s a misunderstanding.”